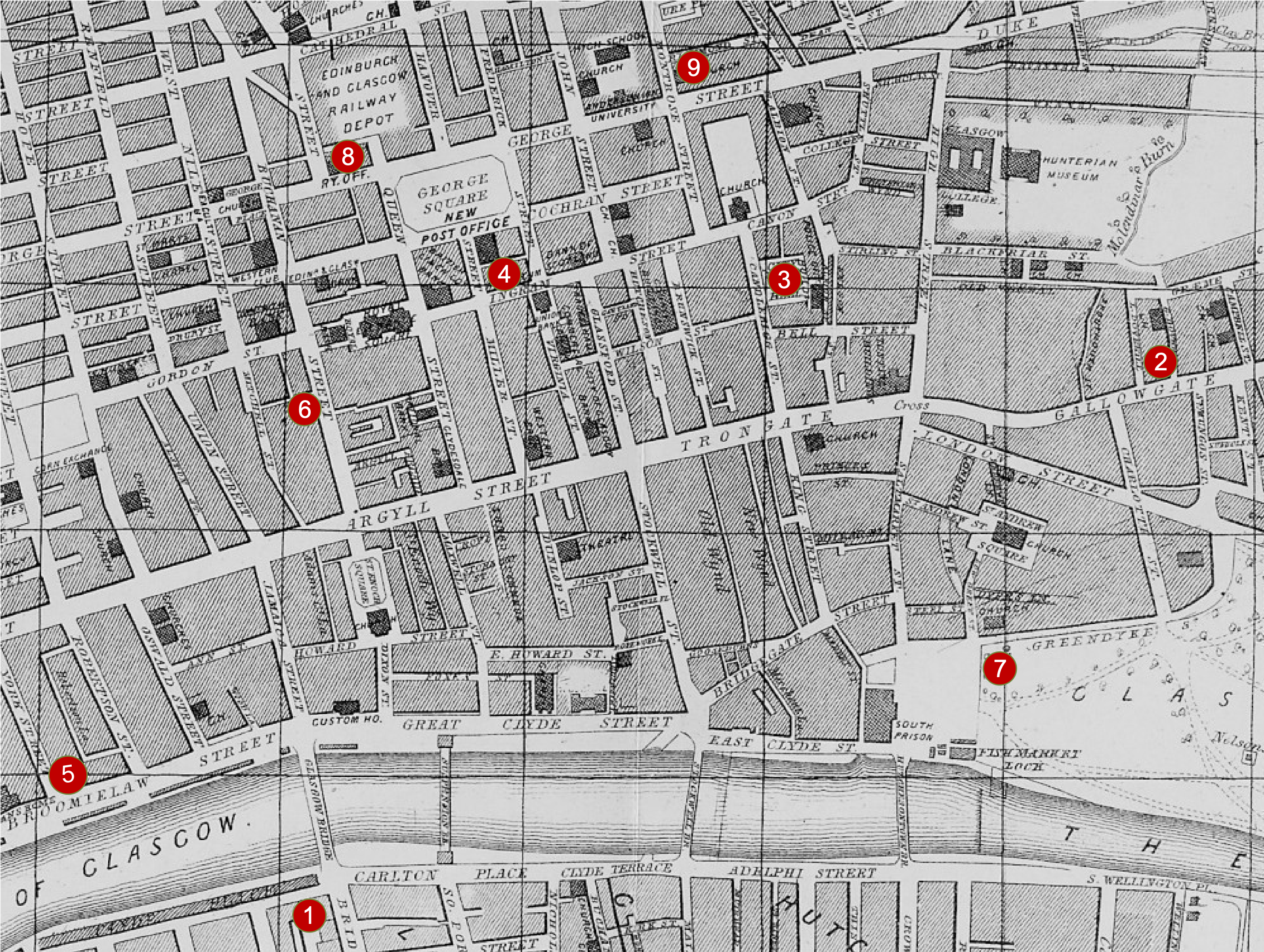

- Terminus of the Glasgow-Ayr Railway.

- 161 Gallowgate.

- City Hall.

- Assembly Rooms, Ingram Street.

- Eagle Temperance Hotel.

- Monteith Rooms, Buchanan Street.

- Adelphi Theatre Royal, Jail Square.

- Terminus of the Glasgow-Edinburgh railway.

- 16 Richmond Street.

Frederick Douglass travelled to Glasgow on Saturday 10 January 1846, sailing from Belfast after an extensive tour of Ireland. He had been invited by William Smeal and John Murray, secretaries of the Glasgow Emancipation Society who had been eagerly anticipating his arrival for some months. A ‘large and respectable’ audience gathered to hear the ‘self-liberated slave’ deliver his first public lecture at the City Hall the following week. This meeting, he recalled later that year

was attended by 1,500 people; our second meeting was much larger, 2,500 being present, and these principally working people. Few learned or reverend gentlemen graced our platform – but the ladies of Glasgow united in rendering us aid.

For the next three months Glasgow served as his main base from which he travelled north to Perth, Dundee and as far as Aberdeen; to Paisley and Ayr to the south; and west to Greenock and the Vale of Leven. On the lecture platform he was usually joined by his companion James Buffum. On several occasions he also spoke alongside the English abolitionist George Thompson, and the American peace campaigner Henry Clarke Wright, who had been lecturing widely in Scotland since late 1844. Douglass returned to Glasgow in the autumn with William Lloyd Garrison from Boston, undertaking his third anti-slavery tour of Britain. His friends the Hutchinson Family Singers – who had sailed across the Atlantic with Douglass and Buffum – also performed for audiences at the City Hall in June.

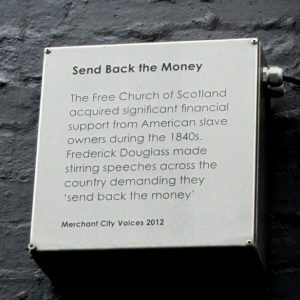

On arrival he would have crossed the Clyde, packed with sailing vessels, some of them bearing slave-grown cotton from New Orleans, offloading their cargo to be consumed by the 150 or so mills in the city and surrounding area. Glasgow’s economy for a long time had relied on imports from the tobacco, sugar and cotton plantations of North America and the Caribbean but Douglass focussed on another connection: the cordial relationship between the Scottish churches and their counterparts in the United States. The main target of his speeches was the Free Church of Scotland, which faced criticism from abolitionists when it accepted donations from Presbyterians in the Southern States and refused to condemn their pro-slavery stance. But – as Douglass continued his recollections:

I was besought not to agitate the question there, and for a time, I confess my hands hung down – I felt almost incapable of prosecuting my work. … I found that nothing was left for me, but to attack that Church boldly, and I at once proclaimed myself ready to go through the length and breadth of the land and sound the anti-slavery alarm, to summon forth the old feeling of opposition to slavery which I knew existed in the hearts of the people of Scotland.

Douglass revitalised the campaign; its slogan ‘Send Back the Money!’ was chanted at meetings, sung in the streets, and scrawled on the sides of buildings.

On a number of occasions Douglass expressed his disappointment that anti-slavery sentiment was not as strong as he expected. ‘Not six years ago there were many in this city who did not hesitate to come forward and avow themselves the uncompromising advocates of emancipation,’ he remarked. ‘Where are they now? They are among the missing.’

And he had sharp words for those who wondered why he was not equally committed to the cause of the working class in Scotland. ‘We have slavery here,’ they say. Douglass certainly ‘did not mean to dispute the existence of much misery and suffering in the country,’ reported the Glasgow Argus, ‘but he denied that they had slavery here.’ Slavery was not merely hardship or the denial of political rights, but the ownership of one human being by another, secured by repeated acts of physical violence. ‘Let one who had felt in his own person the evils of slavery – let the mark of the slave-driver’s lash on his own back – tell them what it was.’

Douglass competed for audiences who flocked to halls and meeting rooms to hear edifying lectures on history, science, literature and religion. He also had to lure them away from lighter entertainments. The celebrated dwarf General Tom Thumb drew crowds to City Hall from January to March, while the African American actor Ira Aldridge appeared at the Adelphi Theatre in February. Glasgow Dramatic Review noted how Aldridge coupled his Shakespearian speeches with renditions of ‘Possum up a Gum Tree’, responding to the popularity of minstrel shows. Indeed, notices for Douglass’ lectures were printed alongside those for the blackface troupe Dick Pelham and his American Sable Brothers – an offshoot of the Virginia Minstrels – offering ‘unrivalled delinations of Negro Life and Character’, illustrating the kind of prejudices the abolitionist had to confront.

|

Terminus of the Glasgow-Ayr railway. Douglass first arrived in Glasgow on the evening of Saturday 10 January on a train from Ardrossan, and passed through the station on Bridge Street again several times during the year. The line was extended over the Clyde in 1879 to terminate at Central Station and Bridge Street station closed in 1905. The site is now occupied by a restaurant. |

|

161 Gallowgate. The home of William Smeal who lived over his and his brother’s grocery store. It would be Douglass’ base in Glasgow for the first three months of the year. He would regularly return there to pick up deliveries of his Narrative shipped from Dublin, which he would then sell at his lectures for half a crown. The site was later occupied by a public house, a chip shop, and today, a cafe. |

|

City Hall. This new civic building, which opened in 1841, was the venue for most of Douglass’ public appearances: in January and February (with Buffum), April (with Buffum, Thompson and Wright), and September and October (with Garrison). His friends, the Hutchinson Family Singers performed here in June. The hall remains a major venue in the city. |

|

Assembly Rooms, Ingram Street. Douglass addressed afternoon meetings of the Glasgow Female Emancipation Society on 18 February and 23 April, in advance of larger public meetings at City Hall. The building was later demolished, but part of the frontage has been preserved as the McLellan Arch on Glasgow Green (pictured here). |

|

Eagle Temperance Hotel. Douglass and Garrison addressed a ‘breakfast party’ attended by ‘seventy friends’ before taking the train to Kilmarnock for an afternoon meeting. The building was later used as a seaman’s mission, and the site is now occupied by a large office block, forming part of the new riverside development on Atlantic Quay. |

|

Monteith Rooms, Buchanan Street. Audience demand for Dick Pelham and his ‘American Sable Brothers’ sustained an extended run here from January to March. The Rooms were built around 1840 and included a large hall used for public meetings, exhibitions and balls; especially popular were panoramas and wax-work exhibitions. They building later housed the offices and printing works for the Glasgow Herald and is currently occupied by retail outlets. |

|

Adelphi Theatre Royal. After an unsuccessful run the previous October, Ira Aldridge returned in February as Zaraffa, Mungo and Three-Fingered Jack, while Douglass was lecturing in Dundee and Arbroath. The large wooden theatre on Glasgow Green, with a capacity of 2,500, was destroyed in a fire in 1848. |

|

Terminus of the Glasgow-Edinburgh railway. A point of departure and arrival for Douglass on several occasions, with four trains a day to and from the capital. The journey took two and half hours, although the new telegraph installed along its route allowed messages to be transmitted in two minutes. Queen Street Station has been substantially redeveloped since the 1840s, none of the original buildings remaining. |

|

16 Richmond Street. Home of Andrew Paton, committee member of the Glasgow Emancipation Society, and his sister Catherine, active in the women’s society. Garrison stayed here in the autumn, and they were close friends of Wright, who also often stayed at their summer residence at Roseneath on the Firth of Clyde. The site is now occupied by University of Strathclyde. |

|

Custom House, Bowling Bay (not on map). Home of John Murray. We know for sure that Douglass spent a few hours here between speaking enagements in Greenock and Paisley in September and it would would have been a natural base for him when he was lecturing in Dunbartonshire in the Spring. The house still stands, overlooking the basin that connects the Forth-Clyde Canal with the river. |

The full text of newspaper reports of Douglass’ 1846 speeches in Glasgow (and elsewhere in Scotland) will be added to this site during 2019. For an overview, see this list of his speaking engagements.