Frederick Douglass’ appearance in Perth on Saturday 24th must have been organised before he had left Liverpool at the beginning of the week, as this notice appeared in the Perthsire Constitutional on the morning of the 21st:

AMERICAN SLAVERY / PUBLIC MEETING in the CITY HALL, on SATURDAY, the 24th current, when Addresses will be delivered by WILLIAM LLOYD GARRISON, GEORGE THOMPSON, and FREDERICK DOUGLASS. Chair to be taken precisely t 7 o’clock; Doors open at Half-past 6; and to prevent confusion. Tickets, 2d each, Reserved Seats, 6d, to be had at the Booksellers.

N.B.-The Committee of the Perth Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society beg to intimate that, before despatching to the Boston Bazaar, the many, various, elegant, and FANCY ARTICLES, which have been so kindly contributed, they will be arranged for public inspection in the GUILD HALL, on Friday the 30th curt., betwixt the hours of 11 and 4.

William Lloyd Garrison who addressed the meeting at City Hall with Douglass, George Thompson and the secretary of the Scottish Anti-Slavery Society, James Robertson, wrote:

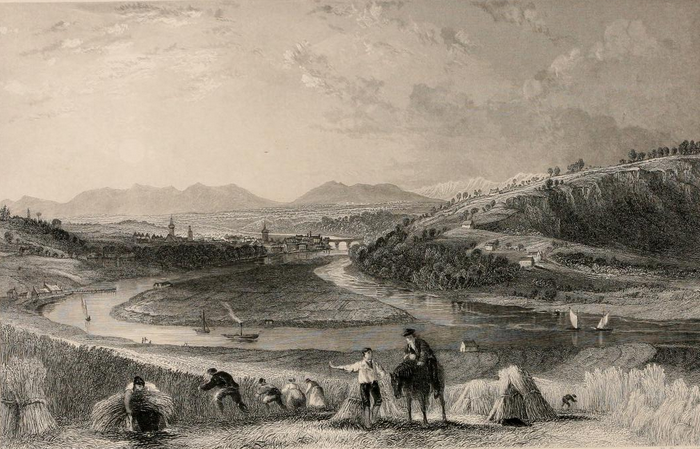

Yesterday, we came to this city, from Dundee, in a steamer borne on the noble river Tay, but the weather was dismal and stormy, so that we lost (what I much desired to see) a good prospect, and saw very little of the river scenery. It was a bad evening for our meeting – for, in addition to the inclement state of the wather, it was Saturday night, preparatory to the administration of ‘the Sacrament,’ and the people were religiously at their several places of worship. We had, nevertheless, about 400 persons present, and a very satisfactory meeting.1

The report in the Perthshire Advertiser gives the impression that only Garrison and Thompson spoke at length, but the Perthshire Constitutional indicates that Douglass made a significant contribution too, delivering perhaps his best-crafted critical response to the debate on slavery at the General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland on 30 May, which he attended.2

ANTI-SLAVERY MEETING

TO REVIEW THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE FREE CHURCH OF SCOTLAND AND THE EVANGELICAL ALLIANCE IN REFERENCE TO AMERICAN SLAVERY

On Saturday evening last, a meeting was held in the City Hall, to hear addresses from G. Thompson and W. L. Garrison, Esqs, and Frederick Douglass, the fugitive slave in impeachment of the conduct of the Free Church of Scotland and the Evangelical Alliance, in having given their sanction to slavery, by receiving slaveholders into Christian fellowship. Owing to this peculiar time of the week, the unfavourable state of the weather, and the occurrence of the sacramental services, the meeting was not so numerous attended as it otherwise would have been. About 500 persons, however, were present.

Mr. Taylor having been called to the chair, made a few preliminary remarks, and introduced to the meeting

Mr. F. Douglass, who, upon rising, was received with much applause. Having made a few appropriate observations in reference to the circumstances which had occurred in connection with the mission upon which he had come to Scotland since he last had an opportunity of addressing the inhabitants of Perth, he was succeeded by

Mr. W. L. Garrison, who, upon presenting himself, was greeting with the warm plaudits of the meeting. He said he was conscious of standing in the presence of men who had most powerfully assisted in the emancipation of 800,000 slaves in the British colonies, and who were opposed to slavery in every part of the world. He himself was an American abolitionist, who had been outlawed by a very large portion of his countrymen because of his love of universal liberty. Why had the people of Great Britain abolished their own colonial slavery? Because they believed it to be a crime against God, and an outrage upon man, to take away the liberty of a fellow-being.

American slavery was even still worse than British slavery. What a spectacle was presented in the year 1846; – men who began their career by proclaiming to the world that they held it to be a self-evident truth that God had made all men free and equal, and had given to every human being the inalienable right of liberty: and yet, that that people, after seventy years of national existence, should be found the possessors of 3,000,000 of slaves, reduced to the condition of things – beings bought and sold, cropped, maimed, branded, driven by the driver’s lash, and hunted by blood-hounds if they should attempt to gain their liberty by flight, and yet, with all that deep depravity, that the Americans should profess to be influenced by the Gospel of Christ, assuming to be the nation of nations, which was destined to diffuse the light of knowledge, civilization, and Christianity, throughout the whole world! (Hear.)

Oh, he (Mr Garrison) was ashmed of his native land, and of those who talked about their regard to Republicanism, and in one hand flourished their bold declaration of independence, and in the other the slave-driver’s whip. If they consented to make a man a ‘thing,’ then it was of no use talking about abuses in connection with that thing. It was of no use speaking of the guilt of taking away the Bible from a thing, of depriving it of the power of learning to read. It was folly to talk about the awful sin of taking away the institution of marriage from a piece of property. No one ever thought of marrying their shovels and tongs, chairs and tables. All the lacerations and other horrors which slavery presented to the world were but the legitimate fruits of the tree.

In consenting to make a man a slave the slaveholders and their apologists had committed the sin of sins against God, and no other sin which it was possible to commit could be added to that sin. He who struck down a human being, and placed him among four-footed beasts, was a man who, of all others, denied God, attempted to dethrone the Deity, and was the greatest Atheist in the universe.

Mr Garrison then read extracts from advertisements respecting runaway slaves, shewing from the published descriptions of their persons, the dreadful lacerations and mutilations to which the slaves were subjected. Not a word was uttered either by the clergy or the Churches against the diabolical system. Men were admitted to the pulpits of all denominations who bought and sold human beings. The American delegates who came over here represented slavery to be a local institution. Those men wanted to be thought good abolitionists in this country. But the truth was, that slavery was a national crime, a national institution, and the whole country were responsible for its existence. Prisons were built for the specific purpose of holding runaway slaves, at the expense of the whole Union, north as well as south.

Dr. Campbell had charged him (Mr Garrison) with being an opponent of religion, but he pronounced Dr. Campbell to be a calumniator and libeller, and the attempt which he had made to support his allegation had covered him with confusion of face.3 The resolution which had been commented upon by Dr. Campbell in the Christian Witness had reference to the slave-holding, woman-whipping, cradle-plundering religion of America, which baptized and sanctified that slavery; while, upon the other hand, the Mahomedan Bey of Tunis abolished slavery and the slave trade throughout his dominions; and the late Pope had warned the faithful under his spiritual jurisdiction to keep their garments free from the sin of slavery.

Mr Garrison having alluded to the circumstances connected with the Free Church’s reception of the money of slaveholders, and extending to them full Christian fellowship in return, besought his audience to raise their protest against that act of the Free Church, and never to cease agitating that question until they had been compelled to send back the money.

Mr Frederick Douglass then came forward and said, – I happened to be in Edinburgh during the last General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland, and then for the first time in my life I had the privilege of attending such an ecclesiastical meeting. I will now state to you the grandest and strongest argument – the argument most loudly applauded in that august assemblage at Canon Mills, in the month of May last, in behalf of American slavery.

I heard the speech of Dr Candlish, and certainly it was Dr. Candlish all over – Candlish at the commencement, Candlish in the middle, and Candlish at the end. It was the most singular, unsearchable, and inscrutable speech I ever listened to. (Hear.) He commenced by stating what he would not do. He would not discuss this question upon any other principles than those ‘great principles:’ by which he meant those principles of Catholicity by which one Church was bound to another Church. He believed that this Church would not consent to discuss the question – that the religious people of Scotland would not consent to discuss the question – ‘upon any other principles than those great principles of Catholicity’ (Laughter.) Over and over again he said ‘he would not consent to discuss this question.’ Still he did consent to discuss it.– He managed to delude his hearers, and continued to mystify the whole question, so that the people when he closed his discourse scarcely knew what side he had taken.

But there was a bold man among them, a Dr. William Cunningham. He was fearless and uncompromising in his defence of the Christian character of the slaveholders. It remained for him to promulgate the blasphemous doctrine that Jesus Christ and his apostles not only invited slaveholders to their communion, but slaveholders who had a legal right to kill slaves. (Cries of ‘Shame.’) He never uttered a whisper of condemnation against them.

I heard that statement myself from Dr. Cunningham. I looked around to see a shudder in the audience. I looked around expecting to behold one universal shudder from the large and apparently intelligent audience. I looked around thinking to find the brows of every man in the audience knit with indignation, that any man should dare to stand up in a Christian assembly in Scotland, and thus libel Christ and his apostles. (Loud cheers.)

But I looked in vain: instead of a shudder of horror, or the loud burst of indignation, shouts of applause were heard on every side. (Hisses and cries of ‘Shame.’) The attempt to bring Christ into fellowship with men-stealers was actually pleaded on the floor of the Free Church General Assembly on the 30th of May last, at Canon Mills. (Cheers.)

But Dr. Cunningham argued the question with Mr. Macbeth. Mr. Macbeth had dared – and it was a bold thing for him to do – to question the soundness of the views of his brother upon this point of man-stealing. He thought that slavery was a sin, and that of necessity, therefore, slaveholders were sinners. Dr. Cunningham took this ground: admitting for argument sake – which he was not altogether disposed to admit – that slavery was a sin, it did not follow that slaveholders were sinners. (Hear and laughter.)

At this point of the discussion all eyes were turned upon the Doctor. He admitted that Mr. Macbeth had stated the subject fairly – (Cries of ‘Oh!’) – that is, the question between the abolitionists and the Free Church was simply this – Is slave-holding necessarily sinful? He should prove that it was not necessarily sinful. Well, the young Free Kirk men, who were sitting all round, seemed astonished at this bold assertion; and they eyed the Doctor to see what great exploit or mighty feat he would do in logic in order to shew, that, after all, slave-holding is not necessarily sinful.

I confess I looked with some degree of solicitude, for I wanted to hear what could be said upon that point, knowing that the Doctor was a very strong and powerful man, both physically and intellectually. (Laughter.)

Well, he supposed a case. ‘Suppose,’ said he, ‘that on the 1st of June next, the Parliament of Great Britain should enact a law declaring all servants slaves to their employers, I then would be a slaveholder, and “by no fault of mine.” “The Law made me a slaveholder.”‘

‘Hurrah, hurrah, my boys!’ said his auditory, ‘the Doctor has proved his point.’ He would not be a ‘slaveholder:’ the law would be the slaveholder.

Well, the Doctor might have sat down at that point and have said to his audience, ‘all further argument is unnecesary; I will submit the case to the jury without any further argument.’

Let us see what this argument amounts to. Why, in order to meet the case it is intended to meet, he must shew that the American slaveholders have, by the laws of America, the slaves imposed upon them, which is utterly untrue. The slaveholders of America themselves make the laws, and among others those by which they hold the slaves. The non-slave-holding part of the population care not a jot or tittle whether the slaveholder holds his slaves or not, so far as troubling themselves to make laws by which the system should be perpetuated. It is the slaveholder who busies himself in obtaining legal enactments by which to enslave his victims, and hold them more securely in bonds.

But suppose the Parliament of Great Britain had, as the Dr. puts the case, passed a Bill consigning all domestic servants as slaves to their employers, and that bill should obtain the royal assent: would Dr. Cunningham dare to sustain the relation of a slaveholder to those domestics? Yes, he would; he has enough of the slaveholder in him to enable him to do that. (Cheers.)

He possesses sufficient of the spirit of the enslaver to permit his sustaining the character of a slave-holder; but the real question is, would Christianity sanction such an act on his part? You know that it would not.

Now let us change the description of sin, and suppose that, instead of slavery, one of the sins comprehended in that most comprehensive crime – for slavery is the sum of all villainies: it is a concentration of violations of all the commands of the Decalogue, not one excepted, – every law of Heaven being broken in the relation of master and slave, – every virtue being broken down, even to the common bond of marriage, as you have already heard – all being swept by the board, and truth, justice, and humanity, all being trampled under foot in the system of slavery; – instead of this comprehensive sin, I say, which Dr. Cunningham would comit in the position he supposes himself placed ‘by no fault of his own,’ we take only one of the sins of which slavery is made up, and test by that single iniquity the soundness of Dr. Cunningham’s position, for if his argument be good in one case, it must be good in another; if sound in reference to one sinful system, it is also true in reference to another sinful system; if it is admitted that what is morally wrong is made righteous by being made legally right. Let us suppose, in the language of Dr. Cunningham that Parliament should enact a law, that upon the 1st of June next all domestic female servants should become concubines to their employers.

‘I then,’ says Dr. Cunningham, ‘should become a fornicator; legally, and by no fault of my own.’ Certainly not, the blame would rest upon the laws! Dr Cunningham would sustain that relation because the law declared its admissibility, because an Act of Parliament justified it. There is nothing in Dr. Cunningham’s speech to lead me to believe that he would not sustain that relation. You will not be shocked at this, my friends. I say there was nothing in his speech to prevent it: for logically he would be bound to sustain that relation. Why not? Is one position less wicked and sinful than the other? Is one sin less revolting to humanity and virtue, and more at war with the eternal mandates of Jehovah, than the other?

Certainly not: every slaveholder is necessarily an adulterer – for what is adultery? It is a disregard of the marriage institution. Every slaveholder in America is an adulterer and a keeper of a brothel. He must of necessity be so because he keeps human beings living in the relation to another where the marriage institution is utterly and entirely obliterated. Go to the plantations of Maryland, and what will you see? Quarters – for what? Where human beings are reared like brutes for the market, without any regard for virtue or marriage; where marriage is actually a crime; where two human beings making a contract with each other and forming a marriage relation, is looked upon as treading against the government of the master. (Hear, hear.)

Do not be shocked, my friends, at the palpable immorality of the case I am supposing. I am merely carrying out the reasoning of Dr. Cunningham. I do not believe, however, that Dr. Cunningham would sustain that relation in all honesty. I believe him to be a holy man, – for he who can apologise for my enslavement, and defend the conduct of my enslavement, although he might profess Christianity until he is black and blue, he will not convince me that he has the spirit of Christianity in him. (Loud cheers.)

I hope I know something of the spirit of Christ. I trust I am acquainted with it by experience. I know that the spirit is love and good will. I know that it proclaims the doctrine of the Deity – doing unto others as we would be done unto. I know it enjoins us to remember those in bonds as bound with them. I know it demands the breaking of every yoke, and the letting of the oppressed go free, and he who strikes hands with tyranny knows nothing of the benignant spirit of Christ. Well, let Dr. Cunningham and his argument go; let the Free Church clap its hands over it – the people of Scotland will see the flimsy character of this miserable sophistry; they will cut it to pieces, and hold it up for ever a brand of infamy by the men who in 1846 could disgrace a Scottish ecclesiastical assembly by making use of so infernal and infamous an argument in behalf of so hellish a system as slavery. When I heard in that assembly argument after argument about involuntary slaveholding, the difficulty of the slaveholder’s position and their ‘unhappy predicament,’ not one word dropped from the lips of this learned Doctor to enforce the observance of that Scriptural injunction, to ‘Remember those in bonds as bound with them.’ No, that was not their purpose; they wanted all their sympathies for the slaveholders.

But a greater [man] than Frederick Douglass is to address you, and I will refrain from making any furter observations.

Mr. G. Thompson, upon rising, was received with loud applause. After alluding to the unfavourable period at which the meeting was held – on the Saturday evening previous to the morrow’s sacrament – he announced that in consequence of the exhaustion of himself and Mr. Garrison, they had been unwillingly compelled to postpone a visit to Aberdeen, where they had proposed to hold a meeting on the Monday, and in order that they might usefully employ the time, they had resolved to hold a second meeting in that hall on Monday evening – (loud cheers) – when he would review the conduct of the Evangelical Alliance upon the subject of slavery – a body whom he had adopted, and whom he meant to pay peculiar attention to. (Laughter.) As advertisements said, ‘nothing should be wanting on his part’ – (laughter) – to give the alliance due publicity.

His friend Mr, [sic] Garrison occupied a position in that country which no other stranger or foreigner ever occupied before him. He came among them with a dearly earned reputation of seventeen or eighteen years’ unremitting toil in the cause of bleeding humanity. He was the sole devoted champion of those who had nothing to give him but their blessings: the love of those whom he had not seen, as well as of all those whom he had seen. In early life he had consecrated himself to the cause of the miilions of his countrymen in bonds; his sympathies at the same time extending to the whole human race, inscribing on his glorious paper, justly termed ‘The Liberator,’ the motto, ‘My country is the world: my countrymen are all mankind.’ (Cheers.)

With the cause also he had embraced the life of the pioneer: toil, proscription, persecution and peril, and the probabilityof a violent death. Not only had he been hunted by the slaveholders, but also by a corrupt priesthood who did their bidding, and who superadded to the malignity of the slaveholder that subtle poison which a corrupt priesthood who alone could administer, in the shape of virulent attacks upon his character, and the holding him up to the anathemas of Christians. If there breathed a man upon the face of the globe who should find a warm welcome from those who love Christ, it was their brother who appeared before them – William Lloyd Garrison. (Cheers.)

But before he left home he had committed the unpardonable offence of daring, single handedly to attack the religious bodies of America. When he looked abroad over the face of that country, to ascertain who were the most determined and successful champions of slavery, he found them to be, not the slaveholders themselves, but the teachers of theology in that country, who had corrupted the word of God, and made the gospel of freedom the handmaiden of slavery. He boldly denounced the pro-slavery religion of America, but carefully discriminatin between pure and undefiled religion and that religion which has been manufactured to serve the special purpose of upholding slavery.

He who troubled the priests of any country rushed into a hedge of briars and thorns. There were no persons in the world more unrelenting than a ministry which had sold itself to work iniquity; and hence those men had for years been endeavouring to blast the reputation of Mr. Garrison in this country by anonymous calumnies, circulated in personal intercourse, in whispers in drawing rooms and vestries, abusing the hospitality of their friends in that country, and poisoning their minds against the advocate of the slave in America, and who for years – and he spoke not unadvisedly, but from actual knowledge upon the subject – had been endeavouring to malign, injure, and destroy the devoted friend of the coloured race.

Great Britain had recently been visited not by a solitary individual who had done the dirty work, but by a cloud of persons from the United States, no less than from sixty to seventy who came over from that country with a deep, settled, determination that whatever else they left undone they would destroy forever the influence and reputation of Mr. Garrison. In America they had been his malignant enemies, fomenting mobs and insurrections for the purpose of effecting his destruction. Those men came over and slandered Mr. Garrison as a man of infidel principles.

He (Mr. Thompson) had mingled with every Christian determination in Great Britain, in all of which he had intimate and endeared friends; he had mingled with the various denominations in the United States, with the missionaries in other parts of the world, and he well knew what infidelity meant in its popular acceptation and its Scriptural and philosophical meaning; and he was there to declare, from a long acquaintance with Mr. Garrison, that he was as far removed from what was meant by infidelity as the arch fiends below were removed in nature and pursuit from the archangels above. (Loud cheers.) The doctrine which Mr. Garrison held upon the question of the Sabbath was the same as that held by Calvin, Luther, Melancthon, Whateley, and others, and had he but held the same views as were held by certain persons upon the question of slavery, the members of the Free Church and the Evangelical Alliance would have pronounced him a good man, and he would have been most acceptable to them.

It would be as reasonable to refuse to sit with a man because your views differed with his upon the subject of phrenology or geology, or other matters of speculation, as to decline to recognize Mr. Garrison as the advocate of the slave because he differs with certain other persons upon the subject of Church government or the Sabbath. There should be a gulf between Christian ministers and the supporters of slavery as wide as the world itself.

It is idle to say that there had existed such a union between the British Churches and the pro-slavery Churches of America for many years: during the last thirty years the ties which bound the denominations in England to those in America had been gradually loosening. At the very time when the Secession Church of Scotland was abjuring for ever all religious intercouse with the slaveholding Churches in America, the leading members of the Free Church in Scotland were unblushingly declaring before the world that they acknowledged the slaveholding Churches of America as in holy communion with themselves.4

For that reason alone, the abolitionists had deemed it their duty to denounce the Free Church of Scotland, nor would they cease their efforts until the people of Scotland had constrained their Free Church to annul the compact into which they had entered, or until the Scottish people had shaken off that Church and left it alone in its unholy confederation with the enslavers of the world.

In America, a population as large as the whole of Scotland were held in chains: what would they say if any body of men were to attempt to enslave them, their wives and children, to the latest generation? Let them remember that it was universally admitted by all enlightened men that without the support of religion, American slavery could not stand. It had been declared by the Rev. Albert Barnes, that no influence but religion could sustain slavery. Let them cease to have fellowship with such a religion as that. (Cheers.)

The Rev. J. Robertson then announced that on Monday, a resolution censuring the Free Church and the Evangelical Alliance for their recent pro-slavery action, would be submitted to the meeting, and on behalf of Mr. Thompson, Mr. Garrison, and the Scottish Anti-Slavery Society he begged to invite any friends of those bodies who chose to defend that conduct to come forward and move such amendment as one might think proper, their platform being open to all.

Thanks having been voted to the Chairman, the meeting separated.

Perthshire Constitutional, 28 October 1846

AMERICAN SLAVERY. – Two meetings were held, one on Saturday, and the other on Monday evening, in the City Hall, to hear addresses on the subject of American Slavery, and the connection of the Free Church and Evangelical Alliance therewith. The addresses were delivered by Messrs George Thomson, Lloyd Garrison, and Frederick Douglass. The audience on Saturday evening would not number more than 350, – that on Monday between six and seven hundred. The speeches were a mere repetition of those delivered by the orators during their last six months’ agitation throughout the country, and with which every one is quite familiar. The conduct of the Free Church was as usual denounced in the most unmeasured terms, as well as the Evangelical Alliance.

Mr Garrison followed Douglass, but with less violence, only affirming that the Free Church, as it had hardened its heart against sending back the money, was going ‘downward, downward to that place where slavery is to be sent in due season.’ He also dwelt at great length upon the horrors of American Slavery, and the support given to the system by the clergymen in the Southern States; and concluded by defending himself against a charge of infidelity which had been insinuated against him by Dr Campbell in the Christian Witness.

Mr Thomson succeeded him, and opened by defending the character of Mr Garrison from the attacks made upon it by different portions of the press, especially in relation to the views he held upon the Sabbath, as what was lawful on one day must necessarily be lawful on any other day. He devoted every day to God. Mr Thomson then said that Mr Garrison held the same views of the Sabbath that Calvin, Luther, Belsham, Barclay, Paley, and a host of other eminent men did. He then proceeded to attack the Free Church, and concluded with announcing another meeting for Monday.

Perthshire Advertiser, 29 October 1846

Notes

- William Lloyd Garrison to Elizabeth Pease, Perth, 25 October 1846, in The Letters of William Lloyd Garrison. Volume 3: No Union with Slave-Holders, edited by Walter M. Merrill (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1973), p. 446

- On the 1846 General Assembly, see Iain Whyte, ‘Send Back the Money!’: The Free Church of Scotland and American Slavery (Cambridge: James Clarke, 2012), pp. 88-94; and Alasdair Pettinger, Frederick Douglass and Scotland, 1846: Living an Antislavery Life (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018), pp. 69-72.

- [John Campbell], ‘Slavery’, The Christian Witness (1 October 1846), p. 486.

- On 8 May 1846 the United Secession Church unanimously approved a motion to withdraw Christian fellowship with the Presbyterian Churches in the United States. The Relief Church approved a similar resolution at its Synod the following week: see, for example, Scotsman, 16 May 1846.