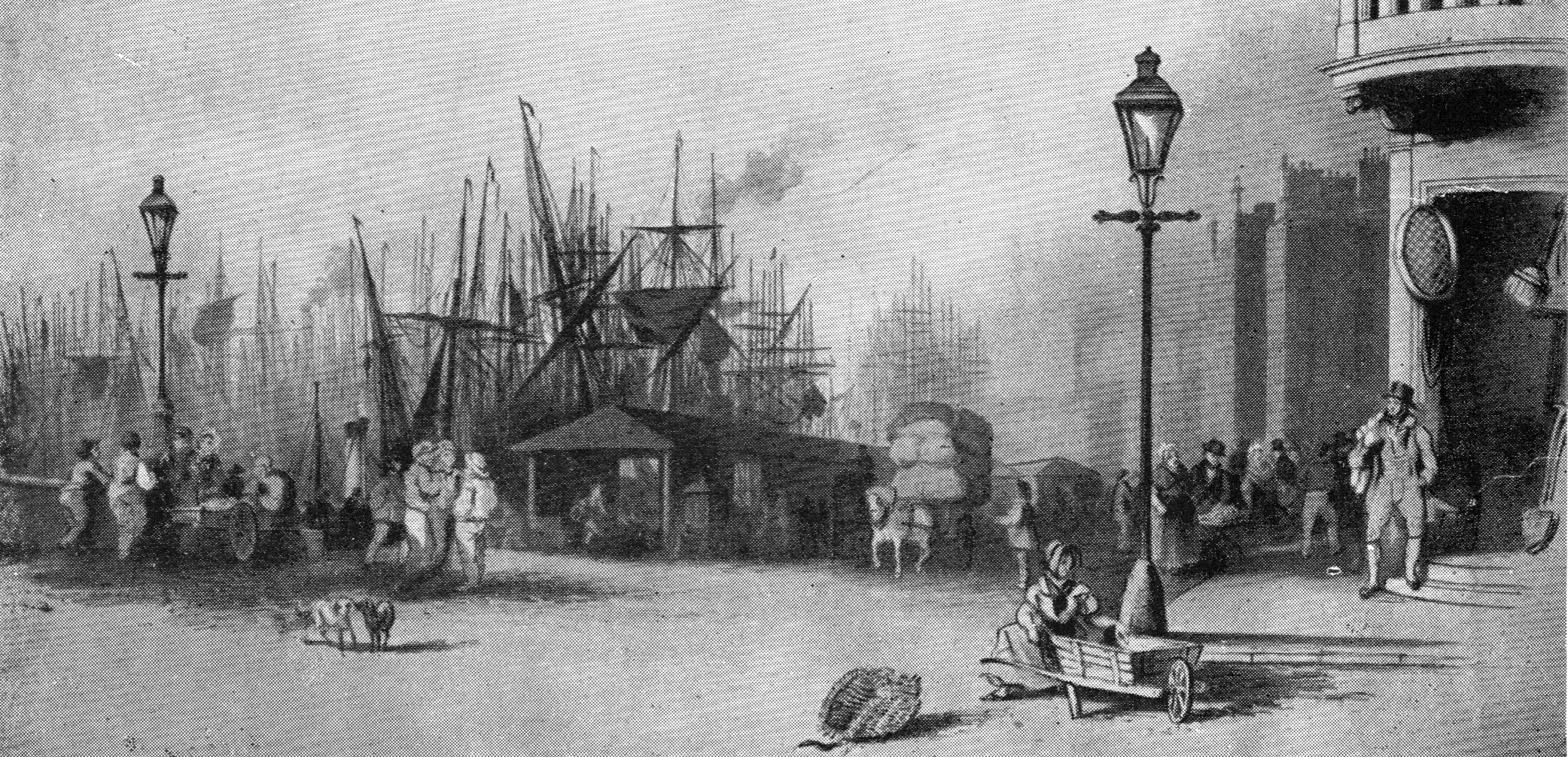

Frederick Douglass and James N Buffum arrived in Glasgow on the evening of Saturday 10 January, having sailed from Belfast to Ardrossan that morning and proceeded by a connecting train.1 Douglass had originally planned to travel to Scotland at the end of November, but, risking the impatience of William Smeal, the Recording Secretary and Treasurer of the Glasgow Emancipation Society who had invited him, he decided to stay in Ireland several more weeks.2 In Glasgow, Douglass stayed with Smeal at his home above his grocery shop at 161 Gallowgate, while Buffum probably enjoyed the hospitality of John Murray, the Society’s Corresponding Secretary, who lived at the Customs House at Bowling Bay, at the western end of the Forth-Clyde Canal, twelve miles west of the city.

Smeal introduced his guests to the committee of the Glasgow Emancipation Society on the Monday evening, to finalise the arrangements for the long-awaited meeting at City Hall on the Thursday.3 Here Douglass would make his first public appearance in Scotland, topping the bill, which announced that ‘Frederick Douglass, a self-liberated American slave, will deliver a lecture on American slavery.’ 4

The hall opened in 1841 and many famous Victorians appeared on its platform, including Charles Dickens, Benjamin Disraeli and William Gladstone. The day before Douglass spoke, a ‘Great Anti-Corn Law Meeting’ was held there. And through January and beyond, Charles Stratton (‘General Tom Thumb‘) drew large audiences, to the delight of his manager, P. T. Barnum. The building, after substantial renovations, reopened in 2003 and is a major concert venue in the city.

The meeting on 15 January was to have been the occasion of a reunion with the peace campaigner Henry Clarke Wright, with whom Douglass had shared antislavery platforms from his earliest days as an abolitionist speaker in Massachusetts, but he could not attend due to other commitments. Douglass and Buffum would meet up with him in Perth, travelling there by coach on Monday 19 January.5

We reproduce the full report of the meeting in the Glasgow Argus (an abridged version of which was reprinted in the Liberator on 15 May 1846), followed by a much shorter summary from the Glasgow Examiner. The report in the Argus concludes: ‘The meeting then adjourned at a quarter past ten o’clock till next evening.’ This suggests that there was a second meeting on the Friday, and the Examiner also hints at there being another when it states that the Thursday meeting was the ‘first of a series’.6 The minutes of the committee meeting of 12 January record a desire to hold ‘another meeting in the City Hall here, or elsewhere, as circumstances may answer, on Friday evening next.’7 However, no firmer evidence has come to light of any further meetings in Glasgow addressed by Douglass until Wednesday 18 February.

For an overview of Frederick Douglass’ activities in Glasgow during the year see: Spotlight: Glasgow.

GREAT ANTI-SLAVERY MEETING

A PUBLIC Meeting of the members and friends of the Glasgow Emancipation Society was held on Thursday evening in the City Hall, to hear a Lecture on American Slavery, by Frederick Douglass, a self-liberated slave from the United States. The meeting was large and respectable. Besides Mr Douglass, and his companion, Mr. James N. Buffum, from America, we observed on the platform a large number of the Committee, and other tried friends of Emancipation; among whom were the Revs. G Jeffrey, Dr. Ritchie of Edinburgh, J. M’Tear, and G. Rose; Councillors Turner and Smith; Messrs. Murray, Smeal, Paton, Ferguson, Ross, Dunn, Anderson, Mathie, Reid, M’Indoe, Cairns, Bland, Barr, &c.8

On the motion of the Rev. Mr. M’TEAR, the Rev. Mr. JEFFREY was called to the Chair.

The Rev. Mr JEFFREY, in opening the meeting, said – Ladies and Gentlemen. I have much pleasure in appearing before you this evening. In ordinary circumstances I prefer a less responsible seat than that which you have assigned me as chairman of this meeting. I have little doubt, however, that the members and friends of the Glasgow Emancipation Society, comprising the large and respectable audience I now see before me, will make my post of service a place of pleasure to me, by their usual decorum and courtesy; and, I need scarcely add, by their wonted warm heartedness in the cause of universal freedom, and devotedness to the grand object of all our exertions – the universal abolition of slavery and the slave trade.

Our society still exists, because that object has not yet been accomplished. Our world is still blighted with the slavery of our fellow men. The existence of slavery gave birth to our society. We have consecrated our energies to effect its universal abolition, and only when slavery has been abolished all the world over shall our work be done and the object of this society be gained. (Cheers.) Its history is not that of defeat, but of success. We can point to the first of August9 as part of its history, and tell exultingly that the soil of Britain and her dependencies cannot be trodden by a slave, for his first step on it is his freedom, and that the flag of our sea-girt isle, find it where you may, flaps to the music of universal emancipation. The history of our success is our motive to exertion. (Applause.) While inhabitants of the British isles we are citizens of the world.

What, then, though British soil cannot be touched without making a slave a freeman, if American soil be still polluted with the footprints of American slavery? If our brethren there – children of the same father, with immortal spirits breathed into them by the same God – are brought to the auction stand and sold as chattels – if the ploughshare of unchangeable desolation is passed with unrelenting cruelty through the tenderest relations of affections and sympathies – if the sex of woman do not protect her from barbarity, nor her infant’s cries from an aching heart, far more awful to the oppressed than death – if the strength of the strong man be made but the means of wearing itself away by intenser throbs of anguish and pain, can we as the friends of the oppressed, sit still and fold our hands in apathy, as if we had no other brethren besides those who tread with us the same soil, and breathe the same air of our own country – the dwelling-place of freedom? (Great applause.)

No, we cannot – we dare not relax our exertions, until another first of August have proclaimed that the land of boasted freedom is the land of real freedom – until the American churches, the bulwarks of American slavery,10 have learned that Christianity which never enchains the body, while it enfranchises the human spirit – until we hear the jubilee trumpet of universal emancipation, and hail the morning of universal abolition, whose first dawn upon our world shall find happy hearts everywhere heaving with the sympathies of the free. (Cheers.)

It is not, however, my part this evening to detain you with remarks of my own, but rather to introduce to you the gentlemen who sit beside me, and for the hearing of whom this meeting has been convened. Allow me to say, in introducing the first of these gentlemen to your notice, that it is easy for us to speak of ‘the woes, the pains, the galling chains, which keep the spirit under,’ and descant upon the ills of slavery.11 We have felt but little of its evils – we have never looked slavery in the face. I have, however, this evening to introduce to you, in the person of him who now sits beside me, one who, for many years, has lived and moved amidst all its sad experiences, and who, having felt the scourge of the oppressor, comes to us with the impassioned eloquence of a spirit rejoicing in its freedom, to plead the cause of his oppressed brethren, and to protest against the injuries inflicted on them in the name of American laws, and under the sanction of the slaveholding, slavery-palliating, slavery-protecting churches of the American Union. (Great cheering.)

I have this day read the published narrative of his life, and deeply has it impressed my mind. You will soon find that he needs no introducing of mine to obtain for himself a place in your estimation. Allow me, then, after reading the letter which I hold in my hand from Mr. Wright, to introduce to you Mr. Frederick Douglass, and he will tell you better than I can the heart-blighting influences of slavery, and the soul-inspiring influences of freedom. (Great applause).

The CHAIRMAN then read a letter from Mr. H. C. Wright, addressed to Mr. William Smeal, in which he stated his utter inability to attend, owing to his previous engagements in the North; but stating that his friend, Mr Douglass, could, far better than he, describe the evils of slavery, &c.

Mr. FREDERICK DOUGLASS said it afforded him great pleasure to meet so many as had presented themselves this evening to hear the wrongs of his fellow-countrymen discoursed upon. He always enjoyed a meeting when it was gathered for any benevolent enterprise whatever, but such meetings as the present he regarded as his own, because their aim was the destruction of the enslavement of his race. Whenever he saw any considerable number – indeed, no matter how inconsiderable the number – gathered together for such an object, his heart throbbed with gratitude to God that there were any to sympathise with those who had been so long neglected.

He came to them this evening for the purpose of giving them an account of American slavery. He had no education to recommend him to their hearing. He had never had a day’s schooling in his life. All the learning or education which he had he had stolen – obtained it by stealth – and they knew that slavery was a poor school for rearing teachers of any kind, not less of what were considered the ordinary branches of education than of morality and Christianity, or indeed of any thing else that was good. He trusted they would indulge him, therefore, and hear him with that patience and indulgence which the nature of his cause would at once suggest to them. (Applause.)

[Becoming an Abolitionist Lecturer]

He would first state the object of his coming before them. He had been a slave in the United States. Indeed, he was still a slave by the laws of the United States, he was still a slave, liable at any moment to be dragged back into the bondage from which he had fled. He was a slave in Maryland, but about seven years ago he escaped from his master and fled to New Bedford, in the state of Massachusetts. There he lived some three years unnoticed by the abolitionists – that is, he was not made prominent by the leading men amongst them. His heart, however, was warm in the Anti-Slavery cause, but he had no idea of being called upon to speak on the subject. At that time he got his living by rolling oil casks on the quays of New Bedford, but in 1841, about three years after his escape from slavery, he attended an Anti-Slavery meeting, where he was called upon by a gentleman who had heard him speak at a meeting of coloured people in favour of abolition, to say something. He was induced by this gentleman, to get up and tell his experience in slavery, and the good effect produced by his narrating the cirumstances of his enslavement induced the leading abolitionists of that place to request him to speak publicly on the question of slavery. (Applause.) He hesitated for some time, because he felt anything which he could say, could be said – and was being said – much better than if it were to be spoken by him.12

He could express his own grievance, it was urged, and his refusing to do so would only tend to confirm the statement that the negro was inferior to the white; but he still felt disposed to keep back, and to leave to his white brethren, who had the time, the talent, and the education necessary for instructing the people on this subject, to stand forward and plead the cause. However, by the importunities of Mr. Garrison, and other leading abolitionists, he was induced to come forward in Massachusetts, and tell the evils of his own experience from time to time. In this way an interest was created in regard to both himself and the cause, but he still found it necessary to keep the public uninformed as to where he came from. He only told them he was a slave, that this was the way he was treated, and that others were treated, but he could not tell them who his master was, as any bad designing person might have sent to his master informing him of his whereabouts and the means by which he might be re-taken into bondage; so he kept the whole matter secret for four years. The enemies of the cause, however, in New England, when exposures of slavery became extensively known to be producing the desired effect, stepped forward and affirmed that he never was a slave. The abolitionists had knocked so much of the rust off him, and polished him to such an extent, that the friends of slavery would not believe he had ever been a slave. When he found out this, he sat down and wrote out his experience of slavery, telling the name of the state in which had had been a slave, the name of the county, the name of the town, and the name of the man who dared to call him his property. (Applause.)13

[Seeking Refuge on British Soil]

He exposed the existence of crime, and identified the perpetrators. This exposed him to the terrible calamity of being dragged back to slavery; and to escape this calamity was one of the motives which induced him to come to this country. He had heard there was no slavery here. He had heard that a slave had but to step upon British soil to be free. (Applause.) He recollected to have read something like the following from one of this country’s most eloquent orators – ‘I speak,’ he says, ‘in the spirit of British law, which makes liberty commensurate with the British soil, and which proclaims to the stranger and to the sojourner that the ground on which he treads is holy, and is consecrated to the genius of universal freedom.’ (Cheers.) He had heard also, that ‘no matter in what disastrous battle a man’s liberties had been cloven down, no matter what complexion he wears, no matter whether an Indian or an African sun had burned upon him and darkened his hue, the moment he steps upon British ground his spirit walks forth in majesty, and he stands redeemed, regenerated, and disenthralled by the irresistible genius of universal emancipation.’ (Cheers.) He came here in pursuit of freedom.14

From the period of his childhood he was satisfied of the wrongfulness of slavery. When he was only seven years of age he was satisfied that it was wrong to hold him in slavery. He belived he had as much right to be free as his little white master; and when he kicked him, he felt he had as good a right as he had to kick again. (Cheers and laughter.) At a very early period of his life, he resolved, come what might, to gain his freedom. (Applause.)

He was glad at being here, where no blood-hound could be set upon his track. He was proud of being amongst them and of perceiving none of those contemptuous, hateful manifestations with which people of colour were looked upon in the United States. In that country, termed the land of the free, and home of the brave, there was no spot of earth where he could stand free. If he went to the far west, he was liable to be enslaved. If he went to the far east, he was liable to be enslaved; and if he went to the far north, he was liable to be enslaved. Wherever the twenty-six stars shone on the blue ground of the American flag, there he was liable to be made a slave. In that vast country, stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean, there was no spot of earth secure for his person – no spot of earth where he could be secure from the attacks of his pursuers, the slaveholders. There was no mountain so high, no valley so deep, and no spot so sacred as to give security to the slave. If he were to go to Bunker’s Hill, where he fought the battle of American freedom, and to clasp the granite shaft which commemorated the achievement of a nation’s independence, there he might be secured and dragged back to the man who claimed to hold him as his property. But this was all about himself, and he had felt it necessary, as a means of introducing himself to the audience, to say thus much respecting his own position. (Applause.)

[The Misuse of the Term ‘Slavery’]

But in advocating this cause on this side of the Atlantic, he had been met by this objection – Why do you come to England for the purpose of talking on the subject of American slavery? We have slavery here, says one.15 Now, he wished to be distinctly understood that, in replying to this argument, or statement rather, he did not mean to dispute the existence of much misery and suffering in this country; but he denied that they had slavery here. While he admitted that they had severe want, poverty, wretchedness, and misery here, he denied that they had slavery. What was slavery? Let the slave answer the question to them. Let one who had felt in his own person the evils of slavery – let the mark of the slave-driver’s lash on his own back tell them what it was. (Applause.) Let one who had experienced it in his own person tell them the difference between American slavery and what, by the misuse of the term, was called slavery in this country. (Applause.)

It was not to work hard. That was not slavery. Indeed, he had worked harder since he became a free man than ever he did before when he was a slave. When he got his freedom he went to work on the wharves in New Bedford, and he worked in a manner which he had never done when he was a slave. (Applause.) He had a wife and little one to take care of and provide for, and this was the mainspring of his actions.16 Before he had been moved to action by the lash; now he was operated upon by the hope of reward and of benefiting those he loved, his wife and child. (Much applause.) In these circumstances there was no work too low, too dirty, too menial for him. He was ready to clean the chimney or sweep the cellar – he was ready for anything – he had a wife and child to take care of. Slavery is not working hard. He did it with delight, and the happiest moments he ever spent in his life was working on the wharves of New Bedford for his wife and child.

Slavery is not to be deprived of any political privilege. It is not to be deprived of the right of suffrage, otherwise all women were slaves, because they were universally deprived of this right. They were wrong when they applied this term to any relations of life in this country. It was not the relation of master and servant – it was not the relation of master and apprentice – it was not the relation of ruled and ruler; but it was the relation in which man was made the property of his fellow-man. It was to be bought and sold in the market: it was to be a being indeed, having all the powers of mind of a man, capable of enjoying himself in time and eternity – it was to take such a man, and make property of him. Having the physical power of a man, he may not exercise it, – having an intellect, he may not use it, – having a soul, he may not call it his own. The slaveholder decided for him when he should eat, when he should drink, when he should speak, and when he should be silent – what he should work at, and what he should work for, and by whom he should be punished. He had no voice whatever in his destiny. This was a slave. Had they any such here? If they had such a system here it ought to be abolished, and he would raise his voice in favour of its abolition. (Applause.)

The slave may not decide who he should marry, when he should marry, how long the marriage contract should last, nor what may be the cause of its dissolution. The blood-minded slaveholder might separate man and wife, sending the one any distance from the other. He might take the child from its mother, hurling it in one direction, and her in another, never to meet again. Those were the peculiarities of American slavery. There was no such thing here. Even the beggar on the street in this country could get what the law allowed him. The poorest mother in the land could clasp her infant to her bosom, and the most lordly aristocrat dared not lay hands on such a being. (Applause.)

[Misrepresentations of American Slavery]

When he came to England he was told they had slaves here. He came here to give them information respecting the slave system in the United States of America. He found there was a want of such information. He found that individuals were circulating throughout this country, as well as in England and Ireland, such misrepresentations of slavery as would have the effect, if believed, of cooling that British indignation against slavery which had existed for so many years. The very ship which brought him to this island, brought also such characters as he had spoken of.

In looking into a review the other day he met with an account of the travels of Mr. Lyell, the geologist, in the United States, and what he had read was well calculated to throw a mask over slavery, and to shade its horrid deformity from the gaze of the world.17 He had been in America. Very true. He had been in the Southern States. All very true. But he might have told them that he had been in the company of slaveholders, that he had been waited upon by slaves, that he had been kindly received wherever he went by the slaveholders, that he was regarded amongst them as one of their best friends – if he had told them all the truth, he would have informed them that he was not only amongst them, but that he became enamoured with them, and that his love for them had misled him as to the character of slavery. For any man to write as he did, showed the greatest ignorance of human nature. He spoke of the contentment and happiness of the slaves. He might as well speak of the happiness and contentment of the drunkard lying in the ditch. Why such a man could not be said to be a man. Show him a man contented in chains, and he would show that his manhood was extinct. He was not a man but a beast who would be contented in slavery.

He had been asked why he had run away, and he had given answers to slaveholders, implying that his master was a kind man, but he did not remember the day when he was at all contented with his condition as a slave. (Applause.) Was it natural to suppose that he would break the arm upon which he depended for existence? There was little truth in this, for not only was the cruelty unnatural, but the whole system was unnatural. (Hear, hear.) It was unnatural for one man to trade in the bones and sinews – the body and soul of another. The system being altogether unnatural, therefore, it required the whipping-post, the cat-o’-nine-tails, and the thumb screws, to keep it from annihilation. (Applause.) It must have these or it ceased to exist.

They would readily admit that he was a man and had rights. He might be asked, how he knew he had rights? He knew he had rights, because he had powers. He had a right to think, because God had given him the power. He had a right to take care of his own person, because God had given him the power of doing so. Man had no right to take that power away, and the man who dared to do so, was a thief and a robber. The American people had taken away from three millions of men and women all the rights of citizens – all the rights of Christians – and all the rights of humanity were denied to them. While the ministers of the gospel were telling them from Sabbath to Sabbath to obey God’s laws, it was a crime to take the means of acquiring a knowledge of these laws. While they were telling them this in a land of civil and religious liberty, there were three millions of people denied the privilege of learning to read the name of the God who made them. (Cries of “Shame.”) The slave-mother, for teaching her child the letters which composed the Lord’s prayer, could be hung up by the neck till she was dead. (Sensation.) The punishment of death was the penalty for a slave-mother teaching her child to read the Lord’s prayer in Christian, democratic America.

[His Mission]

He came here because the slaveholders did not wish him to be here.

He came here, because those in slavery knew that this monster of darkness, which hated the light, and to which the light of truth was death, could only live by being permitted to grope her way in darkness, and crush human hearts, unheard of and unnoticed by the religion and Christianity of the world. (Applause.)

He came here, because slavery was the common enemy of mankind, and because the same principle which enslaved the black man would enslave the white man.

He came here, because slavery was one of those gigantic systems of evil which was sufficient of itself to destroy any nation, and to do all in his power to induce the humanity, morality, and Christianity of the world to rise up and crush this demon of iniquity. (Applause.)

And, as England and Scotland had something to do in the enslaving of his race, he came to ask them to lend a hand in destroying this horrible relation. But, possibly, he was not asked why he came here, but he had been asked in other places that question; and he stated this to satisfy them that he had not been fighting a man of straw.

A question had been put to him, on the part of some of those who had been styled abolitionists – men who had laboured ardently for the emancipation of the slaves in the West India islands – men who had stood on that platform, who had come forward, prominently, when the cause of West Indian slavery was the question – and why were they not still amongst them, giving their blows and dealing their thunderbolts of destruction, as they once did, in a similar cause? He had been asked why he came to them, when the question was one belonging to America?

Why, that kind of reasoning would reduce their sphere of action to very narrow bounds, and would, in effect, leave the matter to be decided by the slave and the slaveholder. Discussion was its death – it could not live in the midst of discussion; but he wished to encircle America about with a cordon of Anti-Slavery feeling – bounding it by Canada on the north, Mexico on the west, and England, Scotland, and Ireland, on the east, so that wherever the slaveholder went he might hear nothing but denunciations of slavery, that he might be looked down upon as a man-stealing, cradle-robbing, and woman-stripping monster, and that he might see reproof and detestation on every hand. (Applause.)

She looked to England for shaping her form of Government to some extent, – and if she had a republican form of Government her statesmen looked to the old world for the wisdom how to conduct it, and on that account they ought to have the right kind of wisdom to bestow upon her. Were they the friends of the slaveholders – were they apologists for slavery – were they in fellowship with the slaveholder – would they enter into fellowship with the slaveholder – would they belong to a church which held fellowship with slaveholders – would they enter into fellowship with the man who would hold fellowship with the slaveholder? – No; they would not enter into fellowship with the men who would hold fellowship with such a man. Who would hold fellowship with him? Who would hold fellowship with the man-stealing, cradle-robbing, woman-beating American slaveholder? (Cheers.)

If they were to assume this ground, they would soon see slavery trembling in its fall. If the people of this country, he maintained, took the stand they might take – which they ought to take, and which the slaves were entreating them to take, by their groans and cries, by the clanking of their fetters, and the rattling of their chains, by their own sense of virtue and of compassion, and which they soon might take – the abolition of slavery in the United States might be a matter of history in six months. (Hear and cheers.)

The slaveholders did not like him to be here. They did not like him to be travelling at large, and thought he was quite out of his place here amongst white people, treated and shook hands with by the white people, as if he were one of themselves. He was quite above himself, they thought, and that he would be better to be taken down a button. (Cheers and laughter.)

[His Treatment on Board the Cambria]

As an illustration of slavery, he would give them an account of his voyage across the Atlantic. He left America on the 16th of August, in the Cambria, commanded by Captain Judkins, and he would tell them something of his treatment on board of that vessel. In the first place, he wished to let them know, that a coloured man was not allowed to take a cabin passage. (Shame.)

So far the corrupting influence of American customs and manners extended, that on the deck of a British steamer, under the British flag, the prejudice was so strong that he could not take a particular passage on board a ship for this country, merely because of the colour of his skin. No objection was urged to his moral character. He came to them recommended, probably, as no other man came on the deck of that vessel, for, previous to his leaving the town of Lynn, a meeting of 1500 people, in a town of only 10,000 inhabitants, was convened to give him a character and a recommendation. (Applause.)

He came certified as a man and a gentleman. For such he had ever tried to demean himself since his escape from bondage. Still he could not take a cabin passage, because a few pro-slavery, cadaverous, lantern-jawed Americans were on board. (Cheers and laughter.) There were a few pale-faced Americans on board, whose olfactory nerves would have been most offended if he had come anywhere in the neighbourhood of them. He was ready to take a cabin passage, and to pay for it, and to behave himself as other men did, but he was refused on the ground that he was a coloured man. (Shame.)

Yes, it was a shame for England so far to lower its dignity as to adopt the prejudices of the slaveholders on board any of her vessels, and to violate the British cross, merely to please the slaveholding, woman-stripping, cradle-plundering Americans. Well, when he got on board he took his position before the mast, and spent his days in the forecastle, feeling quite happy, and what gave him the greatest consolation was, that every revolution of the ponderous wheels of their noble ship bore him farther from the land of those proscriptions which he had then escaped.

During the passage discussions were excited on the question of slavery. An excellent friend of his, Mr. Buffum, was on board at the time, and having a white skin, he felt himself at liberty to go anywhere. It was quite an indorsement, a white skin in America. Those who had white skins might go anywhere, they might even go to Texas, that land of angelic personages. (Cheers and laughter.) As he had said, Mr. Buffum could go anywhere in the ship, but he did not leave him. (Great applause.) He went aft, but he took him with him in his heart. He (Mr. B.) talked with the officers and with the passengers on the question. He raised discussions on the subject of slavery. The discussions by-and-by became very exciting. Indeed, there was a difficulty of talking with his friend on such a subject without getting excited, for he never went for half measures; – to use an Americanism, he always went the whole hog. (Loud applause.)

Having a number of copies of his narrative on hand he put them in circulation amongst the passengers, who became quite interested in him, and he had occasionally visitors from the quarter-deck. Those who came to see him were the most intelligent amongst the passengers; their coming proving them to be that; for it was evident that they came to talk on the question of slavery. (Applause.) At length quite a desire sprung up to hear him speak on the subject of slavery. They learned that he had been a slave, and they wanted to have a sprig of the article. He steadily refused, and he wished them to mark this; because he was misrepresented in America with regard to this point. There he was represented to have put himself forward to speak, but he did not move a single step until he was invited by the Captain to do so. In compliance with his invitation he went upon the quarter-deck.

When they came in sight of the beautiful hills of Dungarvan, and got into smooth water, he complied with the request made by the passengers, and communicated to him through the Captain. He went upon the saloon deck, and was introduced by the Captain. He commenced to speak to them on the subject of slavery – and he might mention the Captain had taken an active part in assembling the passengers. The bell was rung, and the meeting was cried, and he proceeded to lecture.

A number of Americans present seemed determined not to let him speak. (Hear, hear.) These lovers of law and order tried, by the shuffling of their feet, and other noises to prevent him from speaking. But they happened to have on board a company of American singers – the Hutchinson Family – who struck up one of their Anti-slavery songs, which had the efect of stilling the tumult. At the close of the song, he was again introduced to the audience, but he had not spoken two sentences before he was interrupted by one of the American, democratic, Christian, liberty-loving gentlemen, who called out, “It’s a lie.” How fine, how exceedingly gentlemanly, were these American republicans! (Cheers.) He went on, taking no notice of this interruption. But he had only spoken a few other words, when “It’s a lie,” was again bawled out by a Mr. Hazard.

He (Mr. D.) went on to say, that since it was all a lie he had said about slavery and American slaveholders, he would bring before them the slaveholders themselves to testify through their judges, their courts of law, their representatives and legislators, the truth of his statements. He meant to read the law of the United States on the subject of slavery. He never saw creatures so chop-fallen in his life; they might have been beaten with a straw. On his making this announcement a general shuffling of feet began. He proceeded, however, to read some of their most cruel slave laws – laws which, if tried by any other standard, went by the board. While reading, one man rushed up to him, and wished he had him in Cuba. Up came another from Louisiana, and wished he had him in New Orleans. A third started up, and wished he had him in Charleston; but none of them had the folly to wish to have him in old Glasgow.

One man was perfectly amusing. He was a very little man, and he ran about the deck, proposing to be one of a number to throw him over board. (Laughter.) How prudent, how cautious, how calculating, to propose to be one of an indefinite number to pitch me into the sea! (Cheers.) A good man, an Irishman of the name of Gough – a calm, dignified, kind of character – who looked down upon him, just as much as he looked down upon the creature who proposed to throw him overboard, stepped up to the little man, and said, “Have you never thought, my friend, that two can play at that game?” (Cheers and laughter.) He slunk away at the suggestion, and he heard no more of him.

Another man was quite as amusing. His name was Phillippi, and he wanted to prevent him from speaking. Why, he could have taken the creature and thrown him overboard. Of course, he would not have resorted to violence, except they had put hands upon him, and, indeed, he thought that although they had put hands upon him, and that he would have submitted. The captain, who acted under these circumstances like a gentleman, having told this little man to “shut up,” came forward and demanded audience, and addressed those rowdy gentlemen in something like the following terms:– “Gentlemen,” he said, “since I left the wharf at Boston, I have done all in my power to make the voyage a pleasant one. We have had every kind of amusement; we have had conversations of various kinds, singing, and discussions. I have tried to manage so as to please all my passengers. Many of them came to me and asked me to give Mr. Douglass an opportunity to speak, as they were anxious to hear him. I, in obedience to their request, asked him to speak. I introduced him to you. The meeting was summoned here, as the passengers wished to listen to Mr. Douglass; and whoever does not want to hear him can go to some other part of the ship, and let those who wish to hear remain. (Applause.) You have acted derogatory to the character of men, of gentlemen, and of Christians, and I demand audience. Mr. Douglass, you are at liberty to speak, and I will protect you in your right to speak. I am captain of this ship; you are at liberty to speak, and no one shall prevent you.” (Great applause.)

A little man from Philadelphia here stepped up and said he (Mr. D.) should not speak. The captain put him aside, when he put his hand under his coat, and he looked for him drawing out a dagger, but it was a card with a request to meet the captain in Liverpool. “Very well,” replied the captain, “I will be there.” (Cheers and laughter.)

However, these gentlemen continued to show up their democratic injustice till the captain brought them to silence, by first threatening and then ordering the boatswain to produce the necessary implements to put them into irons. That was a new thing under the sun to put white slaveholders into irons! (Cheers.) They had been accustomed to put irons upon black people, but the idea of putting irons upon democratic republicans they could not understand; but seeing the captain was in earnest the creatures began to drop down, and in about ten minutes they had all disappeared. (Loud and continued cheering.)18

[‘A Glorious Change’]

Next morning they arrived at Liverpool, and when they stepped upon the wharf the porters showed as much respect and paid as much attention to the black as to the white man. (Applause.) Two days after that he met with several of those who laboured to crush him in America, and who would have scorned to be seen beside him in that country, on the most perfect equality. This was a most interesting position for him to fill.

In Boston he asked permission to go in to see the wild beasts. Some people said, black men were the descendants of monkeys, and he might be anxious to see some of his relations, according to their account. He was told – “We don’t allow niggers in here.” (Shame.) He went to a Church in New Bedford, and took his stand upon the lower floor, but he was told – “We don’t allow niggers in here.” (Great disapprobation.) He went to the Museum, but was told there likewise – “We don’t allow niggers in here.” He went to the Lyceum, and wanted to hear what was going on, but was again told – “We don’t allow niggers in here.”

But when he came to this country, everything was so changed that he sometimes suspected his own identity. (Cheers and laughter.)

About two days after he arrived in England, having heard a great deal about the ancient city of Chester, and Eaton Hall, the seat of the Marquis of Westminster, he went to see it, and who should he see there but their good friends the American passengers by the Cambria, coming for the same purpose. They were all formed into one party, and shown through the hall. He was never so delighted; it seemed so strange that there was no door-keeper to say, “We don’t allow niggers in here.” (Great applause.) He did not know but he may have been wicked, and felt very proud that day to find himself treated on an equality with American slaveholders themselves, for he almost rubbed shoulders with them, but no one dared to say, “We don’t allow niggers in here.” (Great cheering and laughter.) This was a glorious change, and he felt proud that these men saw the way in which he was treated. They would see from what he related that the spirit of slavery did not leave the slaveholder when he left the American shores; and these persons, in whatever society they passed through, left behind them a streak of pro-slavery.

[The American Churches]

The churches of America were responsible for the existence of slavery. (Hear, hear.) Her ministers held the keys of the dungeon in which the slave was confined. They had the power to open and shut – they had the heart of the nation in their hands – they could mould it to anti–slavery or to pro-slavery, and they had put the pro-slavery impress upon the national instrument which spilled his sister’s blood. To hear a man preach, “Love your neighbour as yourself,” and keep his fellow men in the most cruel bondage – to hear a man preach, “Thou shalt not steal,” who robbed whole hundreds of people of their liberty, and everything else which was worth possessing – and to hear a man tell them, “To search the Scriptures,” who made it death, for the second offence, to teach a child to know the letters which formed the name of the God who made him – (Great sensation and applause.) – how horrible was it to hear a man using Scripture in justification of his cruelties, as a certain Captain Thomas Auld19 did, and saying, “He that knoweth his master’s will and doeth it not, the same shall be beaten with many stripes!” (Cries of “Shame.”) He had heard this with his own ears, and seen it with his own eyes.

He meant, in a future lecture, to give a specimen of American preaching in the peculiar canting tone of these pro-slavery preachers; but, in doing so, he wished to be distinctly understood, that, in exposing the religion of the United States, that he had no intention of aiming a blow at Christianity proper. (Hear, hear.) After making a few observations on the importance of the mission in which he was engaged, to plead the cause of the poor oppressed slave, he concluded his address amidst the most enthusiastic applause.

The Chairman then expressed the pleasure he had enjoyed in listening to the address of Mr. Douglass, and introduced Mr. James N. Buffum, a distinguished abolitionist, who had accompanied Mr. Douglass to this country.

Mr. Buffum shortly addressed the meeting in a very interesting manner on the subject of slavery, the state of public opinion in America, the influence of this country in moulding that opinion, and other topics.

The meeting then adjourned at a quarter past ten o’clock till next evening.

Glasgow Argus, 22 January 1846

MEETING OF THE EMANCIPATION SOCIETY.–On Thursday evening the first of a series of meetings was held in the City Hall, to hear the statements of Mr. Frederick Douglas, a runaway slave, in reference to the state of matters in America — especially in reference to slavery. The eloquent lecturer was listened to with marked attention, and he is to continue till he tell the whole truth he knows in reference to the proceedings of ecclesiastics in connexion with slavery.

Glasgow Examiner, 17 January 1846

Notes

- James N. Buffum to William Lloyd Garrison, Bowling Bay, 14 April 1846 (Liberator, 15 May 1846)

- Frederick Douglass to Richard D Webb, Belfast, 7 December 1845, in The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass. Volume V: Supplementary Volume, 1844–1860, edited by Philip S. Foner (New York, International Publishers, 1950), p. 15.

- Minutes of Glasgow Emancipation Society committee meeting, 12 January 1846 (Smeal Collection, Mitchell Library, Glasgow: Reel 1).

- Glasgow Argus, 12 January 1846.

- The plan was for Douglass and Buffum to go to Perth on 19 January: Minutes of Glasgow Emancipation Society committee meeting, 12 January 1846 (Smeal Collection, Mitchell Library, Glasgow: Reel 1). And it is likely that this plan was adhered to, as Douglass was in Perth on 20 January: Frederick Douglass to Richard D Webb, Perth, 20 January 1846, in The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series Three: Correspondence, Volume 1: 1842–52, edited by John R. McKivigan (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), pp. 80–1. In a letter to James Standfield from Dundee (undated but composed after the second meeting there on 28 January and before the third on 29 January), Douglass wrote: ‘I left Glasgow about ten days ago’ (Belfast Commercial Chronicle, 4 February 1846).

- The Belfast Northern Whig (29 January, 1846) refers to Douglass ‘giving lectures [plural], on the subject of slavery, to large and respectable audiences, in the City Hall, Glasgow.’

- Minutes of Glasgow Emancipation Society committee meeting, 12 January 1846 (Smeal Collection, Mitchell Library, Glasgow: Reel 1).

- Rev. George Jeffrey, Rev. James M’Tear, Rev. George Rose, James Turner, Andrew Paton, William Ferguson, John B. Ross, James Dunn, Ebenezer Anderson, Robert Mathie, James and Robert Reid, and John Barr were all on the Committee of the Society. William Smeal and John Murray were its Secretaries.

- The Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 came into force on 1 August 1834, and the anniversary was celebrated annually by abolitionists on both sides of the Atlantic for the next thirty years. See Jeffrey R. Kerr-Ritchie, Rites of August: Emancipation Day in the Black Atlantic World (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2007).

- Jeffrey is alluding to James Gillespie Birney, The American Churches the Bulwarks of American Slavery (London: Johnston and Barrett, 1840), widely reprinted in Britain and the United States.

- These are lines from ‘March to the Battle Field’, a popular song, written to a Scottish air, by Barry Edward O’Meara, better known as Napoleon’s surgeon.

- Douglass is probably referring here to his first abolitionist speech, made in Nantucket in August 1841. See David W. Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2018), pp.118-19.

- The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Dougass, an American Slave, Written by Himself was published in Boston in 1845. Soon after his arrival in Dublin in September, an Irish edition was issued, with a print-run of 2000, copies of which Douglass sold at his lectures.

- Douglass is quoting from a speech by John Philipot Curran in defence of Archibald Hamilton Rowan at his trial for seditious libel in Dublin in 1784. See The Speeches of the Right Honorable John Philpot Curran, ed. Thomas Davis (London: Henry G Bohn, 1845), p.182. Douglass cites this passage several times in speeches in Britain and Ireland in 1845-47, probably unaware that Curran misrepresented ‘British law’ on this occasion. Although abolitionists widely interpreted the decision of in the Somerset v Stewart case (1772) as guaranteeing the freedom of slaves once they touched English soil, Lord Mansfield’s judgement was limited in scope and did not resolve their status. While some slaves successfully petitioned English courts for their freedom in the years following, others failed. In Scotland, however, the Knight v Wedderburn case yielded a more expansive judgement. See Edlie L Wong, Neither Fugitive Nor Free: Atlantic Slavery, Freedom Suits, and the Legal Culture of Travel (New York: New York University Press, 2009), pp. 21–48.

- The expressions ‘wage slave’ and ‘white slave’ were common currency in Britain, even within the ranks of the Chartists and other radicals, even if they intended to emphasise their own grievances rather than endorse chattel slavery, which most of them abhorred. For instance, the Scottish Chartist Patrick Brewster offered the opinion that ‘the fate of the English working man is worse than that of the Russian serf, the Hindoo pariah, or the negro slave’: quoted in Malcolm Chase, Chartism: A New History (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007), p.307. For a useful survey of mid-century debates over the meaning of ‘slavery’, see Marcus Cunliffe, Chattel Slavery and Wage Slavery: The Anglo-American Context, 1830–1860 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1979).

- Douglass married Anna Murray in New York City in 1838. Their first child, Rosetta, was born in New Bedford in 1839. Lewis, Frederick, Jr, and Charles Remond would follow in 1840, 1842 and 1844.

- Douglass is referring to Charles Lyell, Travels in North America (London: John Murray, 1845). The book was reviewed in Chambers’ Edinburgh Journal, 11 October 1845 (which notes Lyell’s impression that slaves are ‘remarkably cheerful and light-hearted’) and in the Edinburgh Review, January 1846 (which quotes his view that the slaves ‘appeared very cheerful and free from care’, prompting the author to ‘confess, that we are not altogether satisfied with Mr Lyell’s language on this subject of slavery’).

- For more details about the voyage see the documents assembled in the section of this site on Jim Crow in Britain. In October 1845, the committee of the Glasgow Emancipation Society took note of the report in the Liberator of the eventful crossing on the Cambria, and resolved to convey its gratitude to Captain Judkins for ‘his firm and noble conduct’ and to have a notice to that effect published in the Glasgow Argus. Minutes of Glasgow Emancipation Society committee meetings, 17 October, 21 October and 5 November 1845 (Smeal Collection, Mitchell Library, Glasgow: Reel 1).

- Thomas Auld (1795–1880) became the owner of Douglass in 1827; he transferred ownership to his brother Hugh in 1845, from whom British abolitionists purchased Douglass’ freedom in December 1846.

Last updated: 21 January 2025