May Day was a busy day for Frederick Douglass and his colleagues. With James Buffum, George Thompson and Henry Clarke Wright he addressed a Public Breakfast held in their honour at the Waterloo Rooms, followed by another meeting of the Edinburgh Ladies’ Emancipation Society in the same place. In the evening they spoke before an audience of 2000 at the Music Hall on George Street.

We reproduce below the account of all three meetings from the pamphlet Free Church Alliance with Manstealers, followed by a more detailed report of the Music Hall speeches in the Edinburgh Evening Post. A much briefer report of the same meeting in the Scotsman is appended.

For an overview of Douglass’s activities in Edinburgh during the year, see Spotlight: Edinburgh.

PUBLIC BREAKFAST

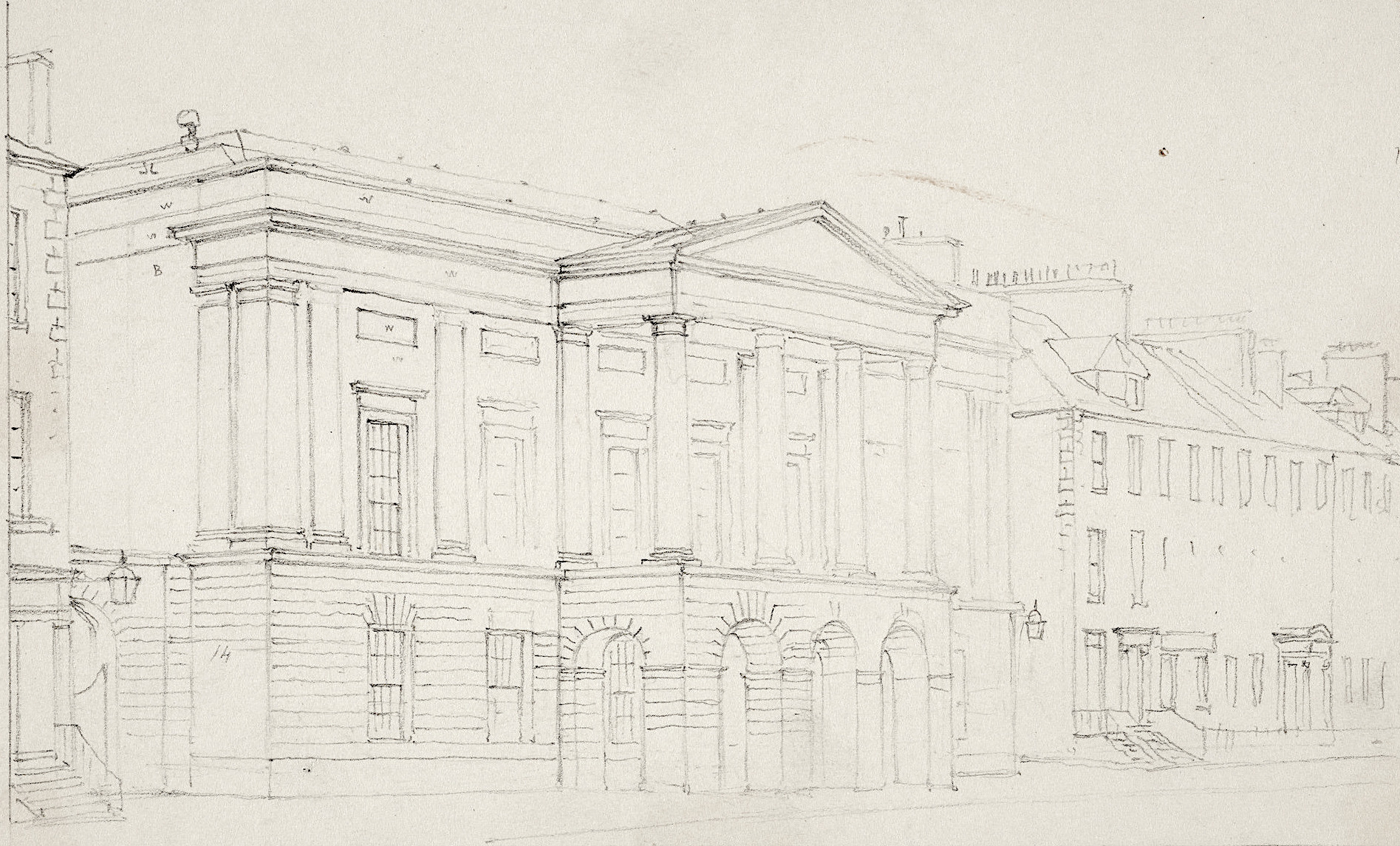

IN HONOUR OF MESSRS. THOMPSON, WRIGHT, DOUGLASS, AND BUFFUM, IN THE WATERLOO ROOMS

Friday Morning, May 1st.

At half-past eight, the Assembly Room was filled with a most respectable audience – JOHN WIGHAM, Junr. Esq. occupied the chair. On his right and left were the guests intimated to be honoured, and a large number of the well-known and most influential friends of the cause of abolition in Edinburgh. At the conclusion of the breakfast,

The CHAIRMAN rose and said – We are met here this morning to pay a tribute of respect and love to those whom we have invited to this breakfast. (Cheers.) They are gentlemen of whom I may say the more see of them, the more we know of their [56] principles and actions, the more we esteem and love them. (Cheers.)

I am sure we all hail with delight the presence of our esteemed friend George Thompson (Loud applause.) We have all witnessed his labours in years that are past, and I do not hesitate to say that, under the guidance of Divine Providence, he has been one of the most efficient instruments in promoting the blessed cause of human freedom. He now appears once more among us in his old character. (Cheers.)

As a member of the Edinburgh Committee, I think we may say we have done what we could. We have sought to place this question of the slaveholders’ money in its true light. You have most of you seen our correspondence on the subject, and I trust have read the excellent pamphlet of my friend Dr. Greville. (Hear.)

At length my friend G. Thompson has come, whose powerful voice is like a six ton hammer. (Laughter and cheers.) He has only been here a few days, but a mighty sensation has been produced, and I doubt not the happiest effects will follow. (Cheers.) It must not be forgotten, that our dear friend is engaged in arduous labours in London, connected with India, especially in his attempts to place a most worthy prince upon his throne, from which he has been unjustly hurled by the East India Company; and I firmly believe that the uncompromising efforts of my friend will be successful.1(Cheers.)

He and our other friends who are from the United States will now address us. We meet for a friendly interchange of opinions, and to learn what we can do for the poor slave. It is my desire that we should welcome and support all who are engaged in the sacred cause of human rights, and prove to them that we have no prejudices which prevent us from cordially co-operating with those who are sincerely and disinterestedly labouring in this vineyard. Let us do what we can, and wish God-speed to all who are struggling for justice to the oppressed.

Interesting addresses were then delivered by Mr. Thompson and his companions.

Mr. Douglass especially enchained the attention of his audience, by the narration of a number of anecdotes relating to himself and other slaves, who had escaped from bondage. This gentleman exercises a wonderful power over the sympathies of his audience. He is alternately humorous and grave – argumentative and declamatory – lively and pathetic. While there is an entire absence of the appearance of any effort after effect, there is the most perfect identity of the speaker with the subject on which he is dwelling, and an extraordinary power of rousing corresponding feelings in the minds of those whom he addresses. This power was singularly manifested on this occasion, and none, we think, who heard him, will ever forget the impression produced upon themselves, or the effect produced upon others.

The entertainment evidently afforded the highest and purest satisfaction to all present. The audience retired at 12 o’clock.

MEETING OF THE EDINBURGH LADIES’ EMANCIPATION SOCIETY IN THE WATERLOO ROOMS

Friday Morning, May the 1st

After the breakfast, the gentlemen who had been entertained, met the ladies and friends of this Society. One of the smaller [57] rooms was crowded to excess. Mr. Wigham again occupied the chair. Mr. Thompson and Mr. Douglass addressed the meeting. At the conclusion of their speeches a resolution was proposed, and carried unanimously, pledging the Society to renewed exertions, and expressive of earnest sympathy with the friends from America, and their co-adjutors on the other side of the Atlantic. A list of names was then taken down of ladies volunteering to furnish contributions to the next Bazaar to the Boston Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society.

MEETING IN THE MUSIC HALL.

Friday Evening, May 1.

This noble and spacious building was crowded to overflowing with a most respectable audience. The admission was by tickets, sixpence each. About 2000 persons were present.

Mr. DOUGLASS delivered a long and eloquent address. The first part of his speech described the condition of the condition of the coloured population in the United States, and the treatment which those persons had received who had nobly sought to succour them. The last part of his address was a severe denunciation of those in this country, who had confederated with the slaveholders of America; and, to hide the obliquity and enormity of their act, had recently employed themselves in defaming, ridiculing, and stigmatising himself and his colleagues. None who heard the withering castigation bestowed by Mr. Douglass on the Rev. Mr. Macnaughtan of Paisley, who had branded him as ‘a miserable and ignorant fugitive slave,’ will ever forget it Poor Mr. Macnaughtan! was the cry of many, while listening to the biting satire and annihilating retorts of the ‘fugitive,’ who charged the reverend sneerer with taking from the sustenation fund, for his own benefit, that which ought to have been applied to the education of his coloured brethren.

Mr. BUFFUM made a short but effective speech.

Mr. THOMPSON followed, but as we understand that gentleman purposes to prepare his speech for the press, we shall not attempt so much as an outline of it Suffice it to say, it was an examination of the opinions of Dr. Chalmers, on the subject of slavery, at various periods during the last twenty years, and an irrefragable demonstration, that Dr. Chalmers is, on the showing of the deliverance of the Assembly last year, a sinner of the deepest dye; inasmuch as he has, throughout his writings, contended for the sacredness of slave property – a doctrine which the Assembly say none can entertain, without being guilty of a sin of the most heinous kind.

The feeling manifested by the audience on this occasion, exceeded that evinced at any of the previous meetings. The exhibition of the view of Dr. Chalmers, contained in his tract, entitled, ‘Thoughts on Slavery,’ and the contrast of these views with the principles laid down in the deliverance, seemed to transfix the audience, with what a person present described, as ‘mute horror. During this part of Mr. Thompson’s address, the emotions of those present were too deep for utterance. The unanimous burst of applause which followed the appeal to the audience, [58] to testify if the speaker had made out his case against the Doctor, proved that the conviction was universal, that such was the fact.

Mr H. C. WRIGHT then proposed the following resolutions, which were adopted by show of hands, not a hand being raised against them, and so far as could be seen, all voting for them.

1st. That the Free Church Deputation, in going to the slave states of America to form alliance with slave-holders, and to share their plunder, virtually rejected Christianity as a law of life; Christ, as a Redeemer from sin; and God, as the impartial governor of the universe – inasmuch as they pledged themselves and the Free Church, whose agents they were, to receive to their embrace as ‘respectable, honoured and evangelical Christians,’ men whose daily life is a denial of the existence of a just and impartial God, and a violation of the fundamental principles of Christianity; therefore, by our respect for man as the image of God, and as our equal brother; by our faith in Christ as our Redeemer; and by our belief in a just and impartial God; we pledge ourselves never to cease our efforts, until the Free Church shall send back the money obtained of slave-holders, and annul her covenant with death, and cease to hold up man-stealers as living epistles for Christ.

2d. That the members of the Free Church owe it as a duty to God and man to come out from her communion, if, after due admonition, her leaders, Drs. Chalmers, Cunningham, and Candlish, cease not to join hands with thieves, and to seek the fruits of their crimes and pollutions to build Free Churches – thus making themselves and all who concur with them accessories to the unutterable horrors of slave-breeding and slave-trading.

What must be the deep conviction, and stern resolution and powerful excitement of the public mind when such resolutions are adopted unanimously by such a meeting, after full and mature consideration? It was the settled conviction of the audience that every slave-holder is a standing type of infidelity and atheism; and that in their consenting to vouch for his Christianity, Drs. Chalmers, Cunningham, and Candlish, do virtually reject Christ as a Redeemer from sin, and deny the existence of a just and impartial God.

Mr. WRIGHT then proposed to adjourn to Tuesday evening, the 5th of May, to meet in the same place, to review the speeches and writing of Dr. Candlish on this great question. (Cheers.) Doctors Chalmers and Cunningham had been reviewed, their apologies for man-stealers fully answered, and their efforts to keep the people of the Free Church in loving communion with slave-breeders and slave-traders had received a merited rebuke. Dr. Candlish had made himself most conspicuous in this conspiracy against three millions of slaves, and in this attempt to introduce man-stealers to social respectability and Christian communion in Great Britain – Let us have one more meeting to consider Dr. Candlish. (Cheers.)

The proposition to adjourn the meeting was received with loud applause. The audience then slowly and quietly retired, as if deeply impressed with the solemnity and weight of what had been uttered.

Free Church Alliance with Manstealers. Send Back the money. Great Anti-Slavery Meeting in the City Hall, Glasgow, Containing Speeches Delivered by Messrs. Wright, Douglass, and Buffum, from America, and by George Thompson, Esq. of London; with a Summary Account of a Series of Meetings Held in Edinburgh by the Above Named Gentlemen (Glasgow: George Gallie, 1846), pp. 55-58.

AMERICAN SLAVERY & THE FREE CHURCH

A fourth meeting was held on Friday evening in the Music Hall, which was crowded to excess in every quarter.

Mr Thompson, in opening the proceedings, stated that arrangement had been entered into for the purpose of placing before the public, in a cheap form, a complete record of the proceedings of the Deputation in Edinburgh and Glasgow; and concluded by introducing to the meeting Mr Frederick Douglas, the runaway slave.

Mr Douglas was received with much applause. He said, that one of the greatest drawbacks to the progress of the Anti-slavery cause in the United States was the inveterate prejudices which existed against the coloured population. They were looked on in every place as beasts rather than men; and to be connected in any manner with a slave – or even with a coloured freeman, was considered as humbling and degrading. Among all ranks of society in that country, the poor outcast coloured man was not regarded as possessing a moral or intellectual sensibility, and all considered themselves entitled to insult and outrage his feelings with impunity. Thanks to the labours of the abolitionists, however, that feeling was now broken in upon, and was, to a certain extent, giving way; but the distinction is still as broad as to draw a visible line of demarcation between the two classes. If the coloured man went to church to worship God, he must occupy a certain place assigned for him; as if the coloured skin was designed to be the mark of an inferior mind, and subject the possessor to the contumely, insult, and disdain of many a white man, with a heart as black as the exterior of the despised negro. (Cheers.)

[MADISON WASHINGTON AND THE CREOLE]

Mr Douglas then alluded to the case of Maddison Washington, an American slave, who with some others escaped from bondage, but was retaken, and put on board the brig Creole. They had not been more than seven or eight days at sea when Maddison resolved to make another effort to regain his lost freedom. He communicated to some of his fellow-captives his plan of operations; and in the night following carried them into effect. He got on deck, and seizing a handspike, struck down the captain and mate, secured the crew, and cheered on his associates in the cause of liberty; and in ten minutes was master of the ship. (Cheers.) The vessel was then taken to a British port (New Providence), and when there the crew applied to the British resident for aid against the mutineers. The Government refused – (cheers) – they refused to take all the men as prisoners; but they gave them this aid – they kept 19 as prisoners, on the ground of mutiny, and gave the remaining 130 their liberty. (Loud cheers.) They were free men the moment they put their foot on British soil, and their freedom was acknowledged by the judicature of the land. (Cheers.)

But this was not relished by brother Jonathan – he considered it as a grievous outrage – a national insult; and instructed Mr Webster, who was then Secretary of State, to demand compensation from the British Government for the injury done; and characterised the noble Maddison Washington as being a murderer, a tyrant, and a mutineer. And all this for the punishment of an act, which, according to all the doctrines ‘professed’ by Americans, ought to have been honoured and rewarded. (Cheers.) It was considered no crime for America, as a nation, to rise up and assert her freedom in the fields of fight; but when the poor African made a stroke for his liberty it was declared to be a crime, and he punished as a villain – what was an outrage on the part of the black man was an honour and a glory to the white; and in the Senate of that country – ‘the home of the brave and the land of the free’ – there were not wanting the Clays, the Prestons, and the Calhouns, to stand up and declare that it was a national insult to set the slaves at liberty, and demand reparation – these men who were at all times ready to weep tears of red hot iron – (cheers and laughter) – for the oppressed monarchical nations of Europe, now talked about being ready to go all lengths in defence of the national honour, and present an unbroken front to England’s might. (Loud cheers.)

But the British Government, undismayed by the vapouring of the slave-holders, sent Lord Ashburton to tell them – just in a civil way – (laughter) – that they should have no compensation, and that the slaves should not be returned to them – (loud cheers) – thus giving practical effect to the great command – ‘Break the bonds, and let the oppressed go free.’ (Great cheering.)

He remembered himself, while travelling through the United States happening, to be the unknown companion of some gentleman inside of a coach. It was dark when he entered, and they had no opportunity of examining into his features; and during the night a spirited conversation was kept up – so much so that he absolutely for once began to think he was considered a man, and had a soul to be saved. (Cheers.) But morning came, and with it light – (laughter) – which enabled his companions to ascertain the colour of his skin, and there was an end to all their conversation. One of them stooped down, and looking under his hat, exclaimed to his neighbour ‘I say Jem, he’s a nigger,’ kick him out.’ (Cheers and laughter.) That was a specimen of the manner in which the outcast coloured man was treated in the land of freedom and liberty. (Cheers.)

[THE FREE CHURCH OF SCOTLAND]

Well, to the land where these things were practised, and practised openly, a Deputation from the Free Church of Scotland came, commissioned to go forth and lift up their voices, and ask aid in defence of religious liberty – the liberty of conscience. They visited the slave States; where they saw God’s image abused, defaced, flogged, driven as a brute beast, and suffered to pass from time to eternity without even an intimation that they had a soul to be saved, – they saw this, and lifted not their testimony against it – (cheers, and cries of ‘shame, shame’) – no comforting hand was held out to the crushed and broken spirit of the slave – (cheers) – but they cringingly preached only such doctrines as they knew would be acceptable to the slaveholder and the man stealer. (Loud cheers.)

He would rather suffer to exhibit on his hands the burning brand of ‘S.S.’ (slave stealer) which some of his abolition brethren could do, and suffer the persecutions and dangers to which they had bee subjected, than bear on his head the sin which lay at the door of that deputation – the moral responsibility which their acts involved, and the respectability which their implied sanction gave to the traffickers in human blood. (Immense cheering, – three distinct rounds of applause.)

The feeling of prejudice, however, against the slave was not altogether confined to the United States – (hear, hear, from Dr Ritchie), – there were men in this country, too, ministers of the Gospel of Christ, who could point the finger of scorn at the ‘fugitive slave.’ There was the Rev. Mr M’Naughton of Paisley – supported by such papers as the Northern Warder and the Witness – who did not hesitate to brand him (Mr Douglas) when he visited Paisley, as a poor, ignorant, miserable fugitive slave – (loud cries of shame, shame); and what more did he say? Did he say that he would ‘send back the money!?’ (Loud cheers and laughter.) No, no, that would have been humbling to him, and insulting to the gentlemen of the New States, for whom he said he had the highest regard. Oh yes, he had given so much ‘regard’ to the purse-proud slaveholder that he had none left to bestow on the poor degraded slave. (Loud cheers.)

Now, he (Mr Douglas) did not expect such things as these when he came to this country – he did not expect to hear them from a minister of the gospel, but least of all did he expect to hear them from the Rev. Mr M’Naughton – (hear, hear,) a minister of the Free Church – man who had loaded his altar with the gold which, produced by the labour of the ‘fugitive slave,’ should have been employed in his education, and yet turns round and calls him ignorant – (loud cheers) – who built his churches with the earnings of the slave – wrung from him amidst tears of blood and sounds of woe – and yet slanders him now as a miserable fugitive. (Immense cheering.) He (Mr D) would not say that to a dog, after having taking his earnings – after having robbed him; yes, it was a hard word, but it was nothing else than robbery, he cared not who took it. (Cheers.)

But when was the money to be sent back? He would tell them; when the people of this country, out of the pale of the Free Church, came to the conclusions he had just shown them – when the full tide of popular indignation – and it was fast flowing just now – (cheers) – will not be withstood by that Church, and when her members became fully alive to the odium and disgrace they are incurring for the sake of clutching the stained hand of the man stealer – then shall the money be sent back. (Loud cheers.)

The present moment was just the very time to consider this question of Free Church contamination. They must not lay all the charge, however, on the United States – the Free Church, as a body, has given a respectability to slavery in American which it never before enjoyed – (hear, hear) – and henceforth they must bear their share of the responsibility attaching to it – the responsibility of the tears, and the agony of the slave; and the crime – the deep, black, damning crime – of the blood polluted man-stealer. (Great cheering, and some hisses.) They might rail against the ‘system,’ but so long as they sanctioned the results of that system they helped to prop up the fabric itself. (Cheers.)

He would go to the next meeting of the Free Assembly, and he believed they would not turn a deaf ear to his complaints. As they had listened to the slave-holder, surely they would not refuse to hear the slave – the ‘fugitive slave.’ (Loud cheers.) As they had received the money of the slaves, surely they would permit him to show cause why they should return it. But whether he should he heard or not, he would be there – (cheers) – and he would take his seat in a place where there would be no danger of his being overlooked or mistaken – for once seen, there was no danger of again mistaking him – (laughter) – and if he was not heard within the walls, he would take care that he would be heard without them. (Cheers.)

There was one thing which he wished to be distinctly understood, namely, that he did not abuse the Free Church for taking the money because she was the Free Church. Had it been the Relief, the Secession, or the Reformed Presbyterian, or even the Established Church itself, he would have pursued towards it the same uncompromising hostility he now showed to the Free. (Loud cheers.) But even now, he began to see something of a right spirit developing itself. Dr Candlish had moved, at a late preliminary meeting of the Evangelical Alliance, that no slaveholder should be admitted as a member. 2 (Cheers.) Why, was it come to this now, that the Evangelical Alliance was to be a purer body than the Free Church of Scotland? Why should the slave-holding, slave-selling minister be allowed to hold ‘Christian fellowship’ with the Free Church, and not with the Evangelical Alliance? – holding him as a brother in Edinburgh, and despising him as a man in Manchester? (Loud cheers.) That was a question which the voice of popular opinion would answer if Dr Candlish would not. He trusted that when the Assembly met, the same reverend doctor would make a similar motion there – repudiate the connection so disgracefully entered into – and SEND BACK THE MONEY. (Loud and prolonged cheering.)

Mr Buffum next addressed the meeting at considerable length, and showed the unmitigated horrors attendant on the slave trade under the very walls of the United States’ Senate, crowned with the emblem of liberty and freedom to all mankind. When he came to Dundee he called on the editor of the Northern Warder, the organ of the Free Church party in that quarter, and endeavoured to reason with him on the subject; but the reasons avowed for taking the money were amongst the most fallacious he ever heard. Had the Free Church not taken the money, they would never have been put to the trouble of inventing such paltry excuses as the following in justification of the course they had pursued.

The extract he would now read them was from the pen of the gentleman to whom he had before alluded: –

So far as we are personally concerned, says he, we must say that few questions have throughout appeared to us more free from difficulty and perplexity. If we want all in a good cause, we shall accept it freely and unhesitatingly from all who tender it. Whatever their creed, or their character, or the origin of their gains, it would make no difference, and constitute no difficulty in our eye, provided that they gave what they gave frankly and unconditionally, and did not ask us to receive it as specially derived from an unlawful source, so as to win from us an implied approbation of that source. If for a good cause, we say, a sum of money were placed in our hands unconditionally and without explanations, we should accept it, whoever the donor, asking no questions, for conscience sake.

But he (the editor of the Warder) went even farther, for he declared that although he had reason to believe that the giver was erring and criminal in some particular part of his conduct, still he would have accepted it – ‘asking no questions for conscience sake.’ (Cheers and laughter.) The article from which he had just quoted concluded by saying, that if the Free Church was to blame in taking the money, the cotton-spinners of Glasgow and Manchester were equally guilty, for they also had at some period made use of money, part of which was subscribed in the Slave States of America. (Laughter.)

Driven from point to point, and from position to position, these upholders of the Free Church had now descended so low as to dispute for character and standing in morality with the cotton-spinners of Manchester and Glasgow. (Great applause.)

Daniel O’Connell, the head of the Repeal agitation, when he was offered the blood stained dollars of the slave-dealer to further his darling project, refused to admit them into his treasury. (Loud cheers.) No, said he, take your money; we will not allow our honest cause to be contaminated with the price of the bodies and souls of the fettered slave. (Cheers.) And he accordingly ‘sent back the money.’3 (Great applause.) Let the Free Church take a lesson from the Irish patriot, and incalculable good would be the result. When the news reached the United States that their money had been refused by the Irish, the Repeal Associations over the length and breadth of the land were smashed to atoms and the agitation completely paralysed, and if the Free Church only followed the example – if they only ‘sent back the money,’ it would go far to strengthen the hands of the Abolitionists and send American slavery reeling to an early grave. (Great applause.)

Mr Thomson said he had received a great number of letters since he came to this city, not only giving him advice how to proceed, but holding out great hopes of his ultimate success. It was impssible that he could answer all these, he took this opportunity of returning his thanks to the writers, and he could assure them that he would endeavour, as far as possible, to carry out their suggestions. (Applause.)

A venerable father of the Free Church stated that if the money was to be sent back, it would not be done by yielding to clamour. Now, he (Mr Thompson) remembered well – it was not so long ago – (cheers) – when Dr Chalmers was as clamorous as any one – (cheers) – and did not hesitate to combine, and agitate, and clamour, through every city and town in Scotland, for the attainment of a great moral object. (Applause.) Let not the Free Church think to put down this agitation by any such means. He had been told that it was resolved on to try their strength on this point; and that they were prepared to say – ‘We won’t send back the money’ at the bidding of clamour, or at the bidding, or because of the unwarranted interference, of a third party. He was old enough to remember greater thanings than that being accomplished against as strong and powerful a body as that clerical triumvirate who were attempting to lord it over the public opinion of the people of Scotland. (Cheers.)

He remembered the time when Catholic Emancipation was carried by popular opinion – when the Test and Corporation Acts Repeal was carried against a majority of Churchmen – when the emancipation of the slaves was carried in the face of the West India interest – when the Reform Bill was passed triumphantly – and at the present moment they see almost abolished the whole system of the Corn laws. (Loud cheers.)

If the force of public opinion, therefore, was able to subdue to its mighty power, the influential party called the West India interest – the boroughmongers of the empire – and even the landed aristocracy of England, surely they need not despair of its influence being felt by Drs Chalmers, Cunningham, and Candlish. (Loud cheers.) Although they did attempt to stem the tide of opinion, he believed there was still as much manly spirit in the Free Church itself as would snap the manacles which this clerical triumvirate were fruitlessly endeavouring to impose on the minds of the adherents to their cause. (Loud cheers.)

Mr Thompson then proceeded, at great length to criticise the conduct of Dr Chalmers in regard to this matter; and contrasted his preface to his last pamphlet, – ‘The Economics of the Free Church,’ with certain opinions promulgated by him on a previous occasion.

At the close of his address, the meeting, which was a most enthusiastic one throughout, separated.

Edinburgh Evening Post, 6 May 1846; reprinted Caledonian Mercury, 7 May 1846

AMERICAN SLAVERY. – A fourth meeting was held on Friday evening in the Music Hall, which was crowded to excess in every quarter. Mr Thompson, in opening the proceedings, stated that arrangements had been entered into for the purpose of placing before the public, in a cheap form, a complete recording of the proceedings of the deputation in Edinburgh and Glasgow; and concluded by introducing to the meeting Mr Frederick Douglas, the run-away slave, who, in a long and eloquent address, pointed out the horrors of American slavery, and declared that if the Free Church were to send back the money, it would go far to strengthen the hands of the American abolitionists, and to send slavery reeling to its grave. Mr Thompson then shortly addressed the meeting; and said that although Drs Chalmers, Cunningham, and Candlish did attempt to stem the tide of public opinion on this subject, he believed that there was still as much manly spirit in the Free Church itself as would snap the manacles which this clerical triumvirate were fruitlessly endeavouring to impose on the minds of the adherents to their cause.

Scotsman, 6 May 1846

Notes

- On Thompson’s interest in India see, Zoë Laidlaw, ””Justice to India – Prosperity to England – Freedom to the Slave!”: Humanitarian and Moral Reform Campaigns on India, Aborigines and American Slavery’, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 22.2 (2012): 299–324 (309–24); Michael Fisher, Counterflows to Colonialism: Indian Travellers and Settlers in Britain 1600–1857 (Delhi: Permanent Black, 2004), pp. 285–8; and Blair B. Kling, Partner in Empire: Dwarkanath Tagore and the Age of Enterprise in Eastern India (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976), pp. 167–78

- The resolution was approved at a meeting of the Aggregate Committee of the Evangelical Alliance in Birmingham in March 1846: see Whyte, ‘Send Back the Money!’, p.120; Richard Blackett, Building an Anti-Slavery Wall: Black Americans in the Atlantic Abolitionist Movement, 1830–1860 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1983), p. 97.

- In a notorious speech at a meeting of the Repeal Association in Dublin on 11 May 1843, Daniel O’Connell declared his intention to refuse ‘blood-stained money’ from pro-slavery Repeal groups in the United States. The speech was reported in the Liberator, 9 and 30 June 1843, and in the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Reporter, 9 August 1843.