(Page last updated 30 January 2020).

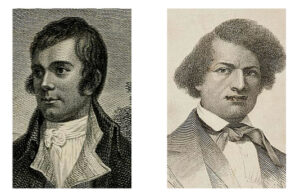

On the 90th anniversary of the birth of Robert Burns, Douglass was invited to address a ‘gathering of the sons and daughters of Old Scotia’ in Rochester, New York. He had moved there with his family from Lynn, Massachusetts just over a year before to set up his own newspaper called the North Star.

We reproduce below the report of the proceedings by Edinburgh-born John Dick, printer of the North Star, who was closely involved in the running of the paper, and contributed numerous articles. From his account, it is clear Dick attended the gathering as a proud Scot and not just as a dispassionate reporter of his employer’s speaking engagements. Two thirds of the three hundred present, he estimated, had been born in Scotland. ‘I could almost have believed,’ he continued, ‘when I heard the Scotch voices, and saw the Scotch faces, and listened to the wild notes of the pibroch, which was played at intervals during the evening, that I was in the “auld toon of Ayr” itself.’

Douglass was never afraid to flaunt his knowledge of Burns. The first book he purchased after escaping from slavery was an edition of James Currie‘s Works of Robert Burns, which he later gave to his eldest son Lewis.1 In Currie’s biographical essay he would have learnt that in 1786 Burns had made plans to emigrate to Jamaica to take up a position on a sugar plantation before the success of his first volume of poems led him to change his mind. That he even entertained such a move may have troubled Douglass, who also may have noted that the abolitionist campaigns of the 1780s and 90s left little trace in his writings. (The song ‘The Slave’s Lament’, often attributed to Burns, did not appear in collections of his work until the 1850s and evidence of his authorship is not conclusive.2).

But when he spoke at Cathcart St Church in Ayr in March 1846 Douglass chose to end his speech by declaring – diplomatically perhaps – that ‘he was proud of having been in the land of him who had spoken out so nobly against the oppressions and the wrongs of slavery.’ And it is a boldly egalitarian Burns who is celebrated in Rochester nearly three years later. In the address by Mr Sidey, which takes up nearly half of Dick’s report, Burns is described as ‘freedom’s poet […] whose greatest joy was in the triumph of right’, who despised British tyranny and sung the glory of the American and French revolutions; a defender of the oppressed and ‘friend to universal brotherhood.’

Yet there is something about Sidey’s speech that may have bothered Douglass. It employs a rhetoric he had heard all to many times in the United States, not least on that other anniversary when patriots commemorate the Declaration of Independence. As Douglass famously pointed out in his ‘What to a Slave is the Fourth of July?’ speech, delivered in Rochester in 1852, the rights it asserted were not extended to members of ‘the negro race,’ and therefore these celebrations take place as if black people do not exist. In that speech he confronts his audience head on: ‘The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me […] This Fourth July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.’ On this occasion, Douglass’ tactics are rather more subtle. Rather than confronting his adversary, he outflanks him.

Like Sidey, he begins by declaring his admiration not for Burns, but for Scotland. Just as Sidey praised the country ‘whose every hill and glen bears record of where a martyr fell and patriot died in defence of freedom and fatherland,’ so Douglass, adapting a turn of phrase he had used before, speaks of how, during his travels ‘through that land,’ he ‘learned that every stream, hill, glen and valley, had been rendered classic by heroic deeds in behalf of Freedom.’3 Coming from Sidey’s lips, this invocation of Scotland does nothing to disrupt the convention that such rhetoric is racially exclusive. But the almost identical words spoken by Douglas have a different meaning; they insist otherwise.

Although I am not a Scotchman, nor the son of a Scotchman […] but if a warm love of Scotch character – a high appreciation of Scotch genius – constitute any of the qualities of a true Scotch heart, then indeed does a Scotch heart throb beneath these ribs.

Only then does he go on to mention his ‘pilgrimage’ to Ayr and have the audience picture him ‘seeing and conversing’ with Burns’ sister. (He gives an account of the encounter in this letter.) In doing so Douglass implies he enjoys a closer connection to Burns than many of those present, making a claim not only to be Scottish but more Scottish than this gathering of emigrants. And then, in a coup de grâce, he fashions the perfect response to those who might suspect this Scottish Douglass is rather far-fetched:

But, ladies and gentlemen, this is not a time for long speeches. I do not wish to detain you from the social pleasures that await you. I repeat again, that though I am not a Scotchman, and have a colored skin, I am proud to be among you this evening. – And if any think me out of my place on this occasion (pointing at the picture of Burns,) I beg that the blame may be laid at the door of him who taught me that ‘a man’s a man for a’ that.’

Part of the force of that reference to those who might have considered him ‘out of my place’ may have derived from his experience at another event in Rochester the previous year when he had been initially refused admission to a celebration of Benjamin Franklin‘s birthday on the grounds that it was ‘a violation of the rules of the society for colored people to associate with whites.’4

On this occasion at least he felt he could expect a warmer reception from the devotees of Burns. As others seemed to do so at another Burns anniversary many years later, where he made a posthumous appearance at the Library of Congress in 2009, in which Scotland’s First Minister, Alex Salmond, invoked Douglass by quoting these same lines, inserting him in a long line of celebrated admirers of Burns, including Abraham Lincoln, Walt Whitman and Maya Angelou.5

BURNS ANNIVERSARY FESTIVAL

This annual gathering of the sons and daughters of Old Scotia in this city and land of their adoption, took place on the evening of Thursday, the 25th inst. There was, for the occasion, a numerous assemblage – not much under three hundred – perhaps two-thirds of them from the land of Burns; the remainder friends and sympathizers.

It was interesting to have an opportunity of seeing and conversing with so many who had visited the ground made classic by the pen of the poet, and who had been reared amid the scenes which he has described with such inimitable power and pathos. I could almost have believed, when I heard the Scotch voices, and saw the Scotch faces, and listened to the wild notes of the pibroch, which was played at intervals during the evening, that I was in the ‘auld toon of Ayr’ itself, within a short distance of the birth-place of the poet, and the scenes of the disasters of his immortal hero, in Alloa [= Alloway] kirkyard. The association recalled to my kind many a barren crag and leafy rivulet, in that brave, old country. Memory was busily at work conjuring up pictures of early days, and the almost-forgotten events of long-past years. As I wandered, mentally, among many a ruin ‘old and hoary,’ and saw the familiar faces of dear friends, some of whom are separated from me by distance, some by death, it would have been strange indeed had I not felt slightly disposed to philosophize on the vanity and changeableness of all things earthly.

This is one – perhaps the principle advantage of such social gatherings. It serves to strengthen the links that bind friend to friend – man to man – country to country. It serves to refresh and water the green spots on memory’s waste, which are apt, amid the business and hurry of this working world, to be lost sight of, if not forgotten.

My present object, however, is not to moralize, but to eke out some account of this anniversary festival. The President for the evening (Mr. Russell) took the chair at eight o’clock, and commenced the proceedings of the evening with a speech, of which the following is the substance:

FRIENDS AND FELLOW-SCOTCHMEN:

This is our second social meeting. – The object of calling our former one, was then briefly explained. We have now the same general object in view – the promotion of social feeling, brotherly love, and innocent amusement. We hope that this, like the former one, will be a scene of happy enjoyment – a scene to be looked back to and remembered as one of pleasant emotion, a green spot in the desert of memory’s waste.

This meeting has been called on the eve of Burn’s [sic] anniversary, to show our respect to the memory of one who has done so much, by his works, to elevate the people of Scotland in their own minds, and in the estimation of the world. Such meetings tend to warm our social feelings. That heart must be cold indeed that does not respond and dilate with the influence of that soul-stirring music and the bright and happy faces around us. We come here to-night with our hearts free from the cares and troubles of the world, determined, for one night at least, to be happy; and when we look upon this meeting in after years, may it be with pleasure and with profit, inasmuch as it tends to make us love our fellow-men more and ourselves no less.

Such meetings are needed in a physical point of view. Our mothers, our sisters, and our wives, are too much confined to their homes, and their minds too much racked with the constant and unceasing watchfulness required in attending to their domestic affairs. I say, and it must be evident to us all that such meetings are needed more than we do have them. We are aware that our health depends a great deal upon the state of our minds. – Should it not admonish us, then, as the warning of a kind parent, to keep our minds buoyant and happy, and on all fitting occasions to meet together in social compact.

After a short interval, during which several songs were sung, and an amusing Scotch piece, purporting to be a dialogue between man and wife, on the propriety of signing the tee-total pledge, was recited by Mr. McWILLIAMS – the Chairman called upon Mr. SIDEY, who spoke as follows:

Mr. CHAIRMAN AND FRIENDS:

This being a social party, we are all expected to contribute our share to the amusements of the evening. For that reason, with your consent, I will make a few remarks. This recalls to mind the joys which we had in our native land – joys which we neither can nor will forget; and he who loves not the home of his childhood, that land which contains the ashes of his sires, is a being whose presence any land can spare. If it looks to its own honor and weal, such a one, the poet has well said, shall die

Unwept, unhonored and unsung.6

All of us who are here, met to spend a night in Scotish [sic] style in the land of our adoption, can look back with pride, to that land whose earliest records give us to know that she alone of nations drove back the troops of the mighty Caesars; and whose every hill and glen bears record of where a martyr fell and patriot died in defence of freedom and fatherland. In this our own time, we can look back to a Watt in Science – a Hume and Macauley in History – a Burns in Poetry. All of her history teems with truths which make her children feel proud of such a native land; and likewise to know that she had some of her sons here when freedom’s foes were strong in their attempts to crush the liberty which Washington so gloriously achieved. – May we never cause Scotland to blush for her offspring in other lands. May we always be found in the van of that march of progress that leaves destroyed in its rear institutions and customs which are a disgrace to the age; and may you always be amongst the first to remove all that degrades our race, or supports a class by practicing an injustice on the many; and may you likewise show that the poet spoke truth when he speaks of home and of birthplace –

That though bleak and barren be the lonely spot,

Its charms can never, never be forgot;7

and when memory leads you back to the haunts of your childhood, may the virtues you saw practiced in the ‘puir man’s hame,’ make you feel as Burns sung –

Time but the impression deeper makes,

As streams their channels deeper wear.8

Ninety years since to-day, Scotland received that child, stamped not with titles or earthly grandeur; but with nature’s mark of genius he was misfortune’s child and Scotland’s glory – nature’s poet and freedom’s poet – a man whose greatest joy was in the triumph of right, wherever asserted. The powerful tyrants of a class government he despised, although at that time his country’s rulers. He could sing the glories of America and the French patriots, even while those glories were reaped at the expense of Britain. – And why? Because he wished to see that principle triumph which says –

Princes and lords are but the breath of kings;

An honest man’s the noblest work of God.9

For such Godlike conduct, he was told his part was to work, not to think. But did he submit? No; he fulfilled his Creator’s plan, that was to set the world a thinking, and mirth a laughing at the baby titles with which born kings decorated the big, but soulless men of his time. When these titles and men are at rest in their kindred clay, Burns’ memory shall be green; and while independence, poetry and benevolence are revered, his memory will be not less so. As long as there is oppression, the oppressed will find in him their defence; and long-faced cant, dressed either as the heavenly chosen or worldly wise, will find such a truth in his poetry as will make them cry, Avaunt – thou art Satan; and while the slave wears the mark of bondage, the songs of Burns will make strong his hope. Where’re freedom finds a home, her praises will be sung with his songs – her brightest robes be independence such as his – her first and proudest worlds –

A man’s a man for all that,10

Burns was a friend to universal brotherhood, an elevator of his race. – He cherished a love for his kind and for freedom, that only found limits where these had no existence. In him we see the victim of the oppressor and the earthly god Mammon. They destroyed the man, but could not crush the spirit which wished and prayed that the time would come

When man to man the world o’er

Would brothers be, and a’ that.11

Let us be like him – in adversity never to think of yielding, but the greater the pressure the greater the strength; and while fortune is kind, like him let us always have a heart to feel and a hand to help the unfortunate.

Before leaving his memory, let us cherish with it the memory of American poets who wreathed around his brows a wreath of poetry which will never fade. So with the words of Halleck, I will leave him where his fame dies not –

And Burns, though brief the race he ran,

Though rough and dark the path he trod,

Lived, died, in form and soul a man,

The image of his God.12

BY ADAM ELDER. – Mr. PRESIDENT: I consider this social gathering as eminently suggestive of thought of the land of our birth, and that of our adoption – suggestive of points of contrast and of agreement, a glance at which many not be inappropriate to this occasion.

Our island home, as she rests, like a wearied dove upon the expanse of waters, presents in territorial extent nothing by which she may become an arbitrator among the nations, or entice to her fields the combatants of the world; though in diversity and grandeur of scenery she yields to none in capacity to charm and captivate the hearts of her sons; nor in the history of martial prowess, since war received its first impulse from the murderous hand of Cain, till the complete development of its enginery under the conduct of Napoleon, have the frequent wars of our country much affected the conduct and destiny of nations; nor in the marts of the business world, have her useful and valuable fabrics, and the extent of her commercial transactions, entitled her to the position of a first power in establishing and maintaining the commercial equipoise, or dictating restrictive measures to estrange mankind; but like many of the choicest enjoyments, the unfolding of her best treasure was deferred until the belligerents in war and its concomitants had proclaimed a truce, and the persuasive voice of home, and school and religion, and the application of these to the practical affairs of life in one short century, has placed our country in the foreground of nations, and Scotland has become a formidable competitor in the discovery and elucidation of principles which are gradually but effectively reconstructing society and religion and governments of the world; demonstrative evidence of which is afforded in the gradual fusion of the diversified character and peculiarity of formerly conflicting peoples, rearing therefrom, as by magic, the present American nation, our adopted home – grander in extent, more potent in power, but dependent alike with the humblest community upon the same fixed rules of action. To us, then, wherever we may go, the discipline of our Scottish homes, and the examples of our countrymen, are an invaluable behest, the application of which, in our American homes, from congeniality, will ensure eminence and respectability.

FREDERICK DOUGLASS, who was present as an invited guest, being called upon by a number of voices, rose and said –

MR. CHAIRMAN: I regard it as a pleasure, not less than a privilege, to mingle my humble voice with the festivities of this occasion. Although I am not a Scotchman, nor the son of a Scotchman, (perhaps you will say ‘it needs no ghost to tell us that,‘) (a laugh,) but if a warm love of Scotch character – a high appreciation of Scotch genius – constitute any of the qualities of a true Scotch heart, then indeed does a Scotch heart throb beneath these ribs. From my earliest acquaintance with Scotland, I have held that country in the highest admiration. As I travelled through that land two years since, and became acquainted with its people, and realized their warmth of heart, steadiness of purpose, and learned that every stream, hill, glen and valley, had been rendered classic by heroic deeds in behalf of Freedom, that admiration was increased. That you may know that I have some appreciation of the genius of the bard whose birth-day you have met to celebrate, I went a pilgrimage to see the cottage in which he was born; and had the pleasure of seeing and conversing with a sister of the noble poet to whose memory we have met to do honor. I can truly say that it was one of the most gratifying visits I made during my stay in Scotland. I saw, or thought I saw, some lingering sparks in the eyes of this sister, that called to mind the fire that ever warmed the bosom of Burns. But, ladies and gentlemen, this is not a time for long speeches. I do not wish to detain you from the social pleasures that await you. I repeat again, that though I am not a Scotchman, and have a colored skin, I am proud to be among you this evening. – And if any think me out of my place on this occasion (pointing at the picture of Burns,) I beg that the blame may be laid at the door of him who taught me that ‘a man’s a man for a’ that.’ (Mr. D. sat down amid loud cries of ‘go on!’ from the audience.)

MR. DEMPSTER, the Scottish vocalist, very opportunely happened to be in the city on this evening, and as became a true Scotchman and admirer of the Scotch poet, hastened to lend the aid of his eloquent voice to add to the interest of the occasion. His ‘Highland Mary brought the sympathizing tear to the eyes of more than one of his delighted listeners; and that song of Burns’ which is, and will always be, the admiration of all men – ‘A man’s a man for a’ that,’ brought raptures of applause from the audience. It was after the singing of this song, that the call for ‘Douglass, Douglass,’ arose,13 and that ‘man for a’ that,’ got upon the platform, and delivered a short speech, of which a sketch will be found above. – Several other gentlemen, and one lady, whose names I did not catch, also volunteered songs. They were all good; but the song by the lady – ‘Let us haste to Kelvin Grove,’ was a peculiarly successful effort.14 The ‘feast of reason,’ was of course the principal part of the entertainment; but Mr Serpell, an English confectioner, who has taken up his residence in this city, to administer to the gastronomical wants of his American cousins, took good care that another kind of feast should not be wanting. May he shadow never be less. The evening passed off pleasantly to all parties. The absence of any beverage stronger than tea, and coffee, prevented the occurrence of any of those scenes that are the bane and the disgrace of social gatherings, in but too many instances, in the land of Burns, much more so formerly than now – though in that respect there is still room for improvement. The assemblage broke up at an early hour, taking with them food for pleasurable reflection, and the anticipation of a future recurrence of Burns’ Anniversary.

– J. D.

The North Star, 2 February 1849

Notes

- The University of Rochester River Campus Libraries’ Department of Rare Books, Special Collections has Douglass’ copy of this edition. Douglass was also presented with another edition when he was in Scotland, inscribed ‘Jany 1846’ by ‘G.C.’ or ‘G.G.’ (the inscription is unclear). This copy is held in the library at the Frederick Douglass home at Cedar Hill, Washington, D.C.

- James Kinsley notes that Burns’ ‘part in this song is uncertain’: The Poems and Songs of Robert Burns, ed. James Kinsley (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968), Vol. 3, p. 1405. According to Donald Low, ‘possibly not his work’: The Songs of Robert Burns, ed. Donald Low (London: Routledge, 1999), p. 547. Gerry Carruthers suggests that ‘the attribution of the words to Burns merits some re-examination and it is possible that Burns merely collected the song’: Gerard Carruthers, ‘Robert Burns and Slavery’ in Fickle Man: Robert Burns in the 21st Century, ed. Johnny Rodger and Gerard Carruthers (Dingwall: Sandstone Press, 2009), p. 167. The new Oxford Edition of the Works of Robert Burns, Vols II and III: The Scots Musical Museum, ed. Murray Pittock (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018) is less sceptical of Burns’ authorship of the song, placing it in ‘Category I or III’ (Vol III, p. 142), Category I being a ‘song wholly by Burns, with no prior antecedents identified, or suspected’, and Category III being a ‘song significantly by Burns, with only isolated lines or a combination of phrases, subject matter, and tune evident from earlier evidence’ (Vol II, p. 12). That it allow the possibility of assigning it to the former is puzzling, given that the notes remark on its resemblance to ‘The Trapann’d Maid’ and ‘The Virginian Maid’s Lament’, suggesting that if Burns had a hand in it, he adapting existing songs rather than composed it anew.

- For earlier uses of variations on ‘rendered classic’ see Frederick Douglass to Francis Jackson, Dundee, 29 January 1846: The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series Three: Correspondence, Volume 1: 1842–52, edited by John R. McKivigan (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), p. 89; Frederick Douglass to Abigail Mott, Ayr, 23 March 1846: Ibid., p. 111.

- William C. Neil to William Lloyd Garrison, Rochester, 23 January 1848: Liberator, 11 February 1848.

- See also Robert Crawford, ‘America’s Bard,’ in Sharon Alker, Leith Davis and Holly Faith Nelson (eds), Robert Burns and Transatlantic Culture (Farnham: Ashgate, 2012), pp. 99–116, which is partly based on a lecture given at the same event and, judging by the similarities, probably shared with Salmond’s speechwriter. For an excellent survey of Burns’ reception in the United States in the 19th century see Arun Sood, Robert Burns and the United States of America: Poetry, Print, and Memory 1786–1866 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018). A detailed account of Douglass’ engagement with Burns is provided in Alasdair Pettinger, Frederick Douglass and Scotland, 1846 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018), pp.135–60, which draws on Michael Morris, Scotland and the Caribbean, c.1740–1833: Atlantic Archipelagos (New York: Routledge, 2015), pp. 98–140.

- Walter Scott, The Lay of the Last Minstrel, VI, i (New York: C. S. Francis, 1839), p. 161.

- John Craig, ‘Memorials of Affection’, in Poems (Edinburgh: John Anderson, Jr, 1827), p. 16.

- Robert Burns, ‘To Mary in Heaven’ in The Works of Robert Burns; with a Complete Life of the Poet (Glasgow: Blackie and Son, 1857), Vol. 2, p. 33.

- Robert Burns, ‘The Cotter’s Saturday Night’ in Ibid, Vol. 1, p. 44.

- Robert Burns, ‘For A’ That and A’ That’ in Ibid, Vol. 2, p. 134.

- Ibid.

- Fitzgreen Halleck, ‘Verses to the Memory of Burns’ in Ibid., Vol. 1, p. cclviii.

- ‘Douglas, Douglas!’ was the war cry of Sir James Douglas (also known as the ‘Black Douglas’) (c1286-1330), ‘the shout with which that family always began battle’: Walter Scott, Tales of a Grandfather (Edinburgh: Robert Cadell, 1836), Vol. 1, p. 142. The slogan figures repeatedly in the earliest historical sources, for example John Barbour, The Bruce [1375], ed. A.M.M. Duncan (Edinburgh: Canongate, 1997), pp. 207, 385, 601.

- ‘Let Us Haste to Kelvin Grove’, The American Minstrel: A Choice Collection of the Most Popular Songs, Gleees, Duets, Choruses &c… (Cincinnati: J. A. James, 1837), p. 29.