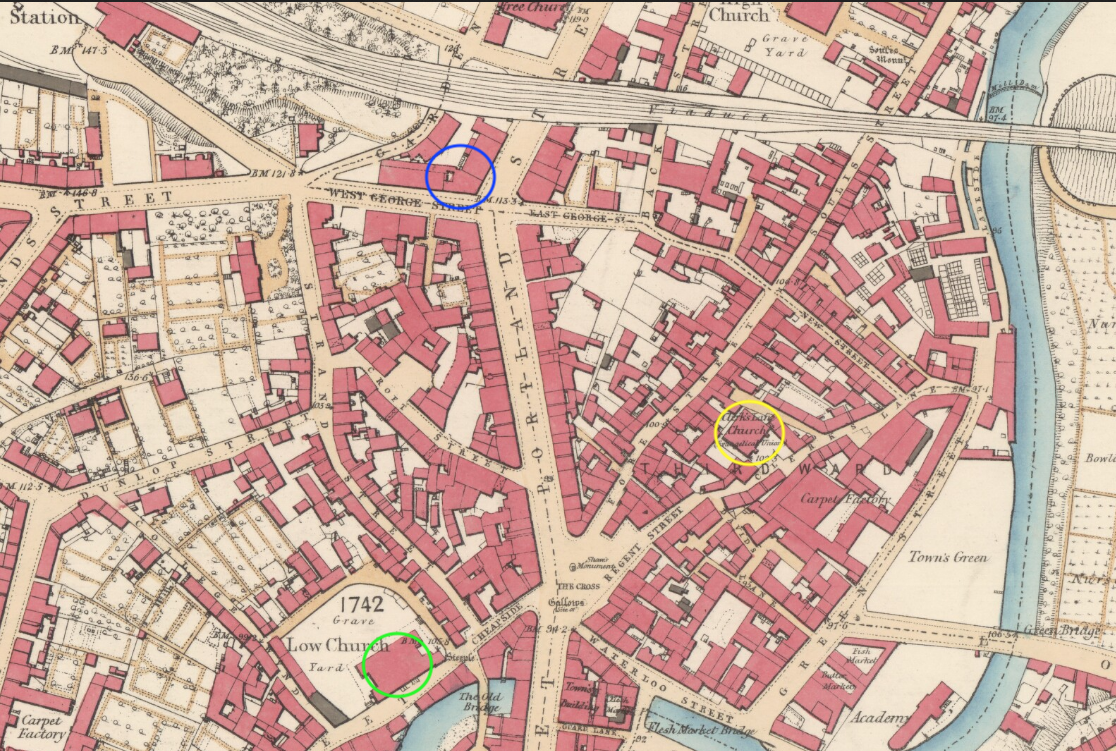

On Friday 17 April, Frederick Douglass and James Buffum spoke at a Soirée held in their honour at the Exchange Rooms on Moss Street, one of the few non-ecclesiastical buildings to have survived from the period.

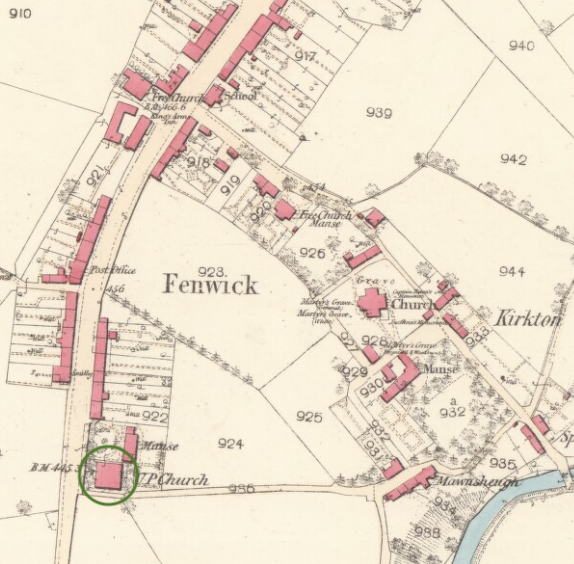

In the ten days since their previous appearance in Paisley, Douglass and Buffum had held meetings in Greenock and Helensburgh, as Buffum indicates in his speech. The meeting at the West Blackhall Street Chapel (later North Church) in Greenock on Friday 10 April was advertised that morning in the Greenock Advertiser, but no newspaper reports of either have come to light.

At the Exchange Rooms, as the occasion demanded, their speeches struck a celebratory note, acknowledging the historical achievements of the British abolitionist movement, from the campaign to outlaw the slave trade (1807) and then slavery itself (1838). Douglass pays particular attention to the ways in which public opinion in Britain had pressured the United States to follow suit, singling out the writings of Charles Dickens, and the protests which greeted the imprisonments of John L. Brown and Jonathan Walker. But there are limits to his admiration. ‘The Americans seemed to speak of a slave as if he were not a man,’ he says. ‘This feeling was not confined to the United States. Some of the people here were almost as bad.’ And Douglass cannot help but return to the issue of the Free Church of Scotland and some of its supporters, namely the minister who wrote scathingly of him and Buffum after attending their meeting in Bonhill.

For an overview of Frederick Douglass’ activities in Paisley during the year see: Spotlight: Paisley.

SOIREE IN HONOUR OF MESSRS. DOUGLASS AND BUFFUM

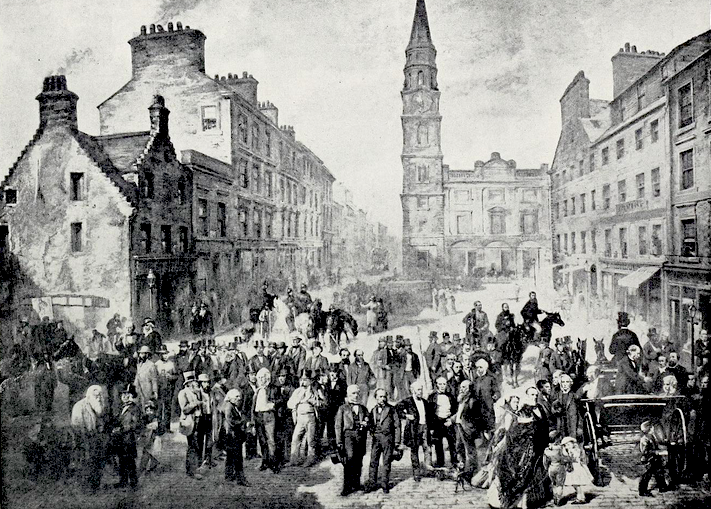

On the evening of yesterday se’ennight, as we noticed in our last, a soiree in honour of the above distinguished advocates of the anti-slavery cause, took place in the Exchange Rooms, Paisley. The room was crowded on the occasion by a most respectable assemblage. Bailie Coats occupied the Chair; supported right and left by Messrs. Douglass and Buffum, Rev. Messrs. Nisbet and Kennedy, Messrs. Caldwell, Nairn, and other gentlemen. Blessings was asked and thanks returned by the Rev. Mr Nisbet.

The chairman then rose and said, that they needed not to be told of the object of the present meeting. They were met to show a mark of respect to two advocates of the cause of humanity. One of these gentlemen could speak as he had done on former occasions of the injuries inflicted on his fellow-men. They have come here that they may raise their voices against that horrid system, American slavery – that they may tell the Americans, that while they have freedom themselves they will not rest satisfied until the foul blot of slavery be erased from the statute book not only of America, but of every nation under Heaven. (Cheers.)

Could there be too much odium cast upon those men who could hold so many thousands of their fellow-men in such abject bondage? The law of God forbid the traffic. Hath not he said, that he has made of one blood all families of the earth? The slave-holder says, no! Christianity forbids it. Did not our Saviour say, ‘do unto others as you would that they should do unto you?’ The laws of humanity forbid it. No system which has the tendency to break asunder the ties of brotherhood – of families – can be a humane one. It would be bad taste in him to occupy their time when such a rich bill of fare had been provided for that evening. The Rev. Mr Kennedy would propose an address to their American friends.

The Rev. C.J. Kennedy said, that he felt honoured on being called to present the address. Long had his heart beat in the cause of freedom – freedom for men of all colours and of all climes, especially freedom for those most oppressed. If there was any spot on earth where freedom should flourish in all its branches that spot was America. It had been held up as a model for other lands. Its institutions had been lauded. Important speculations had been tried there. But, alas! the working out of freedom for the European had led to the bondage of the African in opposition to all the dictates of humanity. It was well that America still regarded this land as the mother country, and although somewhat haughty, looked across the Atlantic to hear what Britons were saying. It was their duty not merely to strengthen the hands of their friends, but they ought also to admonish the Americans. Mr Kennedy then read a long and eloquent address, expressing the utmost abhorrence of slavery, respect for Messrs. Douglas and Buffum, with unqualified approval of the object of their mission. It went on to deprecate all acts of religious communion, either directly or indirectly, with slave-holders, and trusted that the christian honour of Scotland would not be sullied by even the appearance of an alliance with slave-holders. It congratulated Messrs. Douglass and Buffum on the fact, that none of their opponents had dared openly to confront them, wished complete success to their cause, and concluded with the words, ‘Long may your bow abide in strength, and your arm be made strong by the mighty one of Jacob.’

The Chairman then asked if it was the wish of the meeting that the address now read be presented to Messrs. Douglass and Buffum. He asked for a show of hands, when it was unanimously adopted amid much applause.

Mr Douglass, who was received with loud cheering, then came forward and said, – Ladies and Gentlemen, I have seldom stepped on a platform where I desired more to do justice to the cause of which I am a humble advocate, than on the present occasion. Yet I have seldom appeared before an audience less qualified to discharge that duty. I will not, however, apologise further than to say, that previous to coming to this gathering, I felt indisposed to be present at all; but since entering and looking on the right, on the left, in front, and in the rear – (laughter) – I really feel my health has come again. (Cheers.)

I confess, however, that this gathering is one for which I was not prepared. I had not supposed that such a congregation of intelligence and respectability would gather around a poor fugitive slave, to bear what he might have to say, and even to do him honour. (Applause.) If I am not able to do justice to the sentiments in the address, attribute it to the extraordinary character of my position

This is not an evening for entering into any argument on the subject of slavery. You have all signified your abhorrence of slavery, by the adoption of the address now read in your hearing, and it would therefore be like carrying coals to Newcastle to give you a discourse on American slavery. (Laughter.) Our language must be that of happy triumph and glory, and it would not become me to enter into any lengthened details respecting the horrors of slavery. I will call your attention to that brighter aspect of our cause – its progress in the world.

[THE PROGRESS OF ABOLITIONISM]

More than 300 years ago, the slave-trade was not only made legal, but it was also sanctioned and sanctioned by the church. For 200 years the traffic in human flesh was carried on by the christian world unchecked, undisturbed, unquestioned, by any considerable number of the human family. There were, to be sure, occasionally found foes aroused – such as Granville Sharp in this country. It was not till 70 years ago that any stand was taken against the slave-trade, when a number of quakers resolved to form themselves to form themselves into an alliance, and to seek its overthrow.

At this time the whole christian world, was engaged in the trade. It was regarded as a species of commerce as legitimate as any other that then existed. The legislature of various countries legalised it, protected it by their arms, and defending it in various ways. These quakers gathered themselves together from time to time, contemplating the horrors of the middle passage, and resolved to contribute their means to the publishing of tracts, and circulating information throughout the country on the subject. They told their neighbours they were going to work out under God the overthrow of the slave-trade. This was regarded by the multitude as an idle tale – as one of the most foolish attempts ever undertaken by any class of people.

They met from time to time, devising and discussing matters. With hearts devoted to the sacred cause, they went on believing that God would eventually crown their efforts with complete success. There soon sprung up a Clarkson and a Wilberforce, to mention whom ought to produce three rounds of applause. (Great cheering.)

When Wilberforce came forward, public attention became directed to the matter. Ten times did he introduce a bill for the abolition of the slave-trade, and ten times was it doomed to defeat. – Parliament sometimes laying the matter on the table, and at other times giving it an indefinite postponement. Convinced that justice, that humanity, that all nature was on his side, believing that by perseverance he would succeed, he went on with his good work.

And what do we see take place within half a century? We see the slave-trade, which was sanctioned by all Christians, is now nearly regarded as not only improper, but as piracy, and the men caught at it are hung up at the yard-arm.

The cause rolled on till slavery was considered wrong – not only wrong, but sin – a great, a grave, an overwhelming sin – and those sons of sires who had carried it on, now sprung up and sought its abolition. I need only remind you of the means adopted to ensure success – of the nature of the anti-slavery conflict in this country, and I may say that success will follow the use of the same means in the United States as those which were employed here.

Some who hear me this evening remember the debates on the subject of West India slavery. George Thompson went over the length and breadth of Scotland, proclaiming the damning influence of West India slavery. (Cheers.) In this way he did much to remove that foul blot from the character of Britain. Borthwick and others who opposed the success of the glorious cause, are familiar to many who now hear me. But although the cause had to contend against the most adroit talent, against the supineness of the church, and against the indifference of the state, the cause rolled on until, in 1838, eight hundred thousand of British slaves were turned into men.1

I have been asked if I supposed the slavery of the United States would ever be abolished! It might as well be asked of me if God sat on his throne in heaven. So sure as truth is stronger than error, so sure as right is better than wrong, so sure as religion is better than infidelity, so sure must slavery of every form in every land become extinct. Anti-slavery must triumph. God has decreed its triumph. All nature has proclaimed its triumph. So sure as the tears of the slaves are falling, so sure as the groans of the oppressed rend the air with the cry of ‘How long, O Lord God of Sabaoth,’ &c., so sure shall these things come to an end – not by a miracle, but by the forces of truth.

Who can calculate the great good that may result even from the present meeting? Who can calculate the power which such meetings exert in the United States? No slave-holder who may be acquainted with a certain feeling, which must ever accompany a man with a wrong cause. (Cheers.)

When meetings of this kind are held in this country, they confess they feel that the effect is to awaken, to arouse the energies of the humane in the anti-slavery cause in the United States. I believe that slavery is such an enormous system of fraud and wrong, that if once we get the people to see it they will exert themselves for its removal. It would have been long since removed if the honest people had been prevailed on to discuss the matter. I trust we shall now soon succeed in awakening them from their indolence – in rousing them to get the weight thrown off which bears down their moral energies. We have not yet been able to get them to see it – to get them to concentrate their attention upon it. We must get the people to speak about it, preach about it, and pray about it. (Cheers.) In this way we shall get them heartily enlisted in the cause. Some there are in the United States who lay great weight on the public opinion of this country; for you know distance sometimes lends enchantment.2 (Laughter.)

It is so, at all events, in this particular instance. If we wish to call attention to anything, we may point at Britain by reading the writings of such men as Dickens, as well as by the public press. I believe that the notice of Dickens had more effect in calling attention to the subject, than all the books published in America for ten years.3

This is because they have some deference for the opinions of those out of the country. Americans are very peculiar in this respect – for, like the beggar, they like to know what others think of them. (Laughter.) This good or bad trait in Brother Jonathan‘s character, must be made available to anti-slavery. We want to tell them in what light their religion and their institutions are viewed in other lands; and as they look to others we will take advantage of this disposition in effecting the overthrow of slavery in the United States.

Since I came to this country I have been the means of calling more attention to the subject in America, than I could have done had I remained there twelve years. I have been travelling up and down, showing them up in their true colours. I see that the New York Herald is abusing me. The Express, a democratic paper, is denouncing me – all are denouncing me as a glib-tongued scoundrel.4 They say I am speaking against American institutions, and am stirring up a warlike spirit against them. Never, in any instance, have I done this, although, if I were a war man, I might with some degree of pride call your attention to slavery, and urge you, as friends of freedom, in the event of a war, to take advantage of it for abolishing slavery. I have never, in any instance, attempted to stir up their bloody feelings, never advocated the use of means inconsistent with the doctrines of Christianity. I wish to act by the power of truth, to apply undisguised truth to the hearts and consciences of the slave-holders. Slavery is as abhorrent to God, as revolting to humanity, as it is inconsistent with American institutions.

So far from my efforts having the effect of stirring up war amongst the British, they will have the effect of cementing the two nations in the bonds of peace. What are the abolitionists of the United States? Almost all – universally peacemen – as opposed to war as they are to slavery. They are men who cancel the existence of the spirit of war, and who labour to supplant it with the spirit of peace and its attendant blessings.

So far from their being any tendency in our proceedings to war, the very opposite is the effect. (Cheers.)

I do speak against an American institution – that institution is American slavery. But I love the declaration of independence, I believe it contains a true doctrine – ‘that all men are born equal.’ It is, however, because they do not carry out this principle that I am here to speak. I have a right to appeal to the people of Britain – to people everywhere – I would draw all men’s attention to slavery. I would fix the indignant eye of the world on slavery. (Cheers.) I would concentrate the moral and religious sentiment of the world against it, – (great cheering) – until by the weight of its overwhelming influence, slavery be swept from off the face of the earth. (Loud cheers.)

I believe I have a right to do this. God has not built up such walls between nations as that they may not be brethren to each other. I am a man before I am an American. To be a man is above being an American. To be a human being is to have claims above all the claims of nationality. (Loud cheers.) But I have no nation. America only welcomes me to her shores as a brute. She spurns the idea of treating me in any other way than as a brute – she would not receive me as a man. (Shame, shame.) The last steamer from America brings word that my old master, Mr Auld, has transferred his right of property in me to his brother Hugh. Oh! what poor property – (laughter) – and if I ever step on American soil he will have me. In case Frederick return to America, he will spare no pains or expense to regain possession. (Laughter.) This reminds me of the man who told his wife that he saw a rainbow running round. His wife, however, could not see it. It was running round and round, and the man said always he would catch it next time it came round. Mr Auld will catch me the next time I go round. (Laughter and cheers.)

Mr Buffum said he could not but reflect this evening on how changed were their circumstances from what they were in time past, accustomed as they had been to the abuse of the American people, being considered beneath the notice of those who held themselves to be respectable. But a short time had elapsed since they came to this country. They were received with great distinction by those whose notice was desirable. But three years ago he was dragged out of a railway car in America for being a friend of Frederick Douglass.5

However, on the night previous to their leaving the United States, there was a large meeting called in the town where they resided, for the people to express their opinions in regard to them – to express their sympathy with them as men, and to bid them God-speed in their progress through this country. The meeting was held in a large hall, and such was the interest excited, that hundreds had to go away for want of room. He had no language to express the feelings of his heart on that occasion. He felt exhausted when he came there. He had been speaking with his friend Douglass for a fortnight, and on one occasion Frederick was so exhausted that he had to leave a meeting to his charge. Mr Douglass had told him to speak on this occasion of the moral effect of such meetings as the present. He wished he could do justice to this thought. He wished he could get them to know the moral effect of that meeting. When they saw such a one as Frederick had shaken himself free from bondage – when they saw him show up the horrors of American slavery, he did not expect that it would go across the Atlantic, and have such a powerful effect.6

When they came on the deck of the British steamer they found men of all kinds on board. They found slave-holders and anti-slavery men on board. They found the Hutchinsons singing their anti-slavery songs. Then they had a speech from Frederick, at which the slave-holders made a row. The report has gone across the Atlantic, and stirred the country from one end to the other. They talk of rebuking Captain Jenkins for insulting the dignity of the American people by allowing him to speak.7

When they arrived at Dublin they had anti-slavery meetings attended by most respectable people. The Lord Mayor had attended, and was so well pleased that he made a public dinner, and invited the Corporation, while Douglass and he had attended as guests. That dinner was reported. It went across the Atlantic, and the Americans say he must be a curious sort of Mayor who would be instructed by Frederick Douglass. Then Daniel O’Connell had a great meeting in Conciliation Hall. It was crowded, and what should happen but that Daniel O’Connell invites Frederick to make a speech? He came forward, and there was another bombshell struck into Jonathan.8 He did not believe that the countenance they received was for themselves, but on account of the principles they advocated. He was certain that every demonstration of the present kind would be felt on the other side of the Atlantic, and would make the slave-holders feel that their doom was soon to be sealed.

They had visited many towns in Scotland, and they had found but one solitary opponent. They had been at Greenock. They had intimated there that they would consider the conduct of the Free Church, and also of Dr. M’Farlane. They called upon the doctor or any of his friends to come forward in defence. The result was that the minister of the church where their former meeting was held refused to give it. He supposed that in consequence of this they would have to go back to Glasgow. They had, however, got the established church. It was magnanimously given without any charge. They sent the bell round, and had a very large meeting. They discussed what Dr. M’Farlane had said about the Free Church being ‘very much a creature of circumstances.’ They challenged any member of the Free Church to come forward and defend the doctor; and who should come to his aid but Alexander Campbell the socialist?9 They told him, however, that they did not come to discuss socialism, but American slavery. At the close of that meeting a Free Church deacon came forward and said to him, I want you, Mr Buffum, to know that there are Free Church deacons who have no language strong enough to express their abhorrence of slavery. It was a great sin, and he would not defend it, nor the conduct of Free Churchmen in holding communion with those who were engaged in the traffic.

Greenock was aroused, and they next went to Helensburgh. At the close of Mr Douglass’ address there was an individual came forward and said that they were animated with a bad spirit, a spirit of hatred to the Free Church, and that they were grossly ignorant of the facts on which they spoke. He charged them with saying that the money was put into the sustenation fund, when it only went into the building fund. They soon turned the tables on him. They told him it mattered not which fund it went into, if it went to the coffers of the Free Church. When the vote was taken on the question there was not a single individual against them – even the gentleman himself did not hold up his hand against them. (Cheers.)

He wished to engage their sympathies on behalf of the poor down-trodden slave. When they came to consider what the subject is, they found it one which ought to enlist all right feelings in its behalf. They used no weapons but the weapons of truth. Last year, then the Americans annexed Texas, they came out at Washington and fired a hundred guns, and said that what they had done would be greatly against the cause of abolition. He could have told them they would have been better to have saved their gunpowder, and to have fired it over the grave of slavery; for he believed that slavery was soon to die.

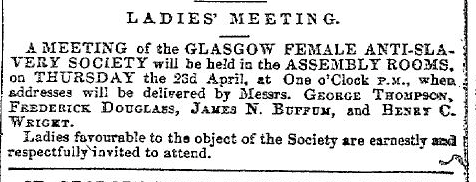

His friend Smeal had told him that there would be a large meeting in Glasgow next week, where George Thompson and Henry C. Wright would be present, and where a remonstrance on the subject of slavery would be adopted, to be signed by all who go for the abolition of slavery. He was to be the bearer of that remonstrance to America on the 1st of August.10 He would hold it up and tell the Americans that Scotland is not represented by the Free Church. (Loud and long continued cheering.) Henry C. Wright was to go home with another next fall, and he hoped they would all sign it. (Loud applause.)

He saw by a report of the Missionary Society, that Dr. Wood was supported by Dr. Chalmers in not giving bibles to slaves, and that it was concurred in by the General Assembly of the Free Church. (Cries of shame, shame.) He hoped the people of that connection would do themselves the justice TO SEND BACK THE BLOOD-STAINED GOLD and be on the side of the slave. (Cheers.)

Mr Frederick Douglass, who again came forward amid loud applause, said, that if he did not make a good speech this time, it would not be their fault, as they had given him so much to eat. If he did not work well with it, it would be an argument for the slave-holder (laughter), who gives his slaves an insufficiency of food. They had gone to the opposite extreme. He felt that their cause would have justice, so far as the present company was concerned.

[THE CASES OF JOHN L. BROWN AND JONATHAN WALKER]

He would go on the same strain as his friend Buffum in reference to their influence on American slavery, and there was no fact which would illustrate it better than the case of John L. Brown, in the State of South Carolina. He had a sister a slave, and as she was anxious to obtain her freedom, he consented to aid her in her escape from slavery. He wrote her a pass and promised to render her whatever other assistance was in his power. She was overtaken in her escape, and John L. Brown was at once arrested, and thrown into prison on a charge of negro-stealing, and the law in South Carolina – remember christian America – the penalty by the law is death for a man to allow a slave to escape. (Shame.) John L. Brown was to be hung – his sentence was accompanied by the judge with a religious parade to the said John L. Brown, telling him that he had violated the law of the land, that he was a young man, and probably a dissolute one, or else he would not have been found in such an act. (Shame.) The sentence was published, and public attention was called to it. For doing an act which all heaven was arrayed in smiles, for extending a helping hand to a perishing sister, for attempting to deliver the spoil out of the hands of the spoiler, was this young man sentenced to death. (Shame.)

It spread across the Atlantic with electrical rapidity. The attention of Parliament was called to the matter by Lord Brougham, who characterised it as one of the most horrible things ever done in a christian country. His denunciations were carried back on the wings of the press. A remonstrance was adopted at a meeting held in the city of Glasgow, and the effect was indeed great.11 The sentence was commuted to a public whipping. This young man was to be publicly whipped on the bare back for having dared to perform this noble deed of benevolence and kindness. He could almost see the fiendish glee with which the slave-holders surrounded their victim on this occasion. His back had not become hardened by whipping, like the slave’s, as he was a free man. With the eye of the christianity and philanthropy of England, Ireland, and Scotland, fixed upon them, if they had dared to proceed in their infernal course of conduct, they would have been held up to the indignant scorn of the whole civilized world. (Cheers.) Latterly the sentence was commuted altogether – and this showed them the power which they possessed. They could paralyze the arm of the wretch who would apply the lash to the flesh of the slave.

There was one Jonathan Walker who went into Florida to sell his craft and cargo. He sold his cargo, but not his craft. While he was among the slaves in that State he spoke to them of a crucified Saviour. He spoke to them of religion. They were converted. He prayed with them and treated them as brethren. When his business there came to an end, the slaves were so attached to him that they went down to the shore of Florida. They did not go to expose him to peril, but their eyes, their tears, their position as they stood on the shore, convinced him that they desired to be free – that they longed to be on a shore where they could worship God according to their consciences. He said if they came into his craft he would take them where they would enjoy freedom, but at the same time he told them he risked all he held dear in the attempt. He, however, believed that if there were any one in the world who desired to be free, and if he could aid him to obtain his freedom, it was his duty to do so, seeing that all should do as they would wish to be done by. The slaves stepped on board. The wind wafted them from the shore.

They had been four days out when adverse winds came upon them. They were caught by an American vessel. They were dragged back to an American port, and thrown into prison for having dared to make any efforts to gain them freedom. The slaves were all whipped. Jonathan Walker was ready to lay down his life that others might take theirs up. Jonathan Walker, a living representative of their blessed Saviour, was willing to suffer that others might be saved. He had to suffer in prison. He was chained to a bolt until the chains wore into his ancles and his legs. When christians in this country heard of this, they spoke in such terms of Jonathan Walker as to direct admiration to him. What was the result? He grew too big for his chains. They found that if they did not desist from their bloody doings, America would be regarded as a murderer – as one who visited a benevolent deed like the most awful crime. Although they did not release Jonathan Walker, as in the case of John L. Brown, he believed he would have died but for the attention of the people of this country. He was sentenced to be branded with S.S., put into the stocks, and sent back to prison. The old gentleman had grown grey in deeds of benevolence, and was for this last act of humanity placed in the stocks. At his bald head was thrown egg after egg: as he stood in the stocks he was beat by the multitude at pleasure. After this he was carried to a post, his limbs closely confined, and the branding iron red hot applied to his forehead. The multitude came rejoicing as they looked at the S.S., and cried slave-stealer.

This was an illustration of the American character. It was done as a national deed. In it they might see the nature of the morality, and the humanity, and the christianity of the American people. (Shame, shame.) In that single S.S. might be read the true character of the American people. They branded him as a slave-dealer [sic]; but the abolitionists of the United States say they intend to make the letters read slave-saviour. People will look back on the bloody nation who did this deed as being a nation of slave-stealers. Jonathan Walker is now at liberty, walking up and down, holding up his S.S., proud of having suffered so much in the cause of freedom, to the shame and disgrace of America – to the confusion of America and the American slave-trade – in defiance of the spirit of oppression which is abroad. He wished Jonathan Walker were here to show the christianity of the men who do such things. Jonathan Walker felt that he was bound by the ties of Christianity to extend a helping hand to his brethren – (cheers) – and for doing this act of christian sympathy he was sentenced to be whipped, imprisoned, and branded with S.S.

The Americans seemed to speak of a slave as if he were not a man. Rev. Mr Wood had said, what was tantamount to declaring that he could see no difference between a slave and a box of goods. This feeling was not confined to the United States. Some of the people here were almost as bad. He had that day seen an article about Buffum and himself in a Free Church paper. The writer seemed to be very much horrified at their expressions in regard to the Free Church of Scotland; and he goes on in the strain of a slaveholder. He even in an indirect way threatens to send me back. (Laughter.) The sly reptile, however, did not give his name. The letter was really a literary phenomenon. (Laughter.) He then read the following:–

SIR, – Happening to be in this town last evening, and to hear that the celebrated Douglass, ‘the self-liberated slave,’ and Mr Buffum were to lecture on the horrors of slavery, and that they had been successful in other places, I went for once to hear them.

I had frequently heard of the horrifying details they give, but they came full up to the mark, and doubtless conclude that their cause is as triumphant. My objects in writing to you now are to request of all and sundry who hear these men to remember that there are generally two ways of stating every controversial subject; that the public here, and especially the working classes, should postpone their judgments, and withhold their opinions until they have heard both sides. For my own part, having heard the subject discussed during eighteen months in the city of New York, and seen the moral and religious character of the proprietors of the Southern states blackened by every means that self-interest and the vilest hypocrisy could devise, and after having been as well informed as I could be of the parts which these proprietors take in advocating the interests of the white labourers and mechanics of the Free States, I came to the conclusion that they have far the better side of the question. Yes, sir, I have come to the conclusion, however unpopular it may be with those deluded by Douglass and his constituents, that the slave proprietors of the Southern states are incalculably more the friends of civilization on these grounds than they are.

I have not at present time to bestow, but I hope to have, and I would advise the semi-savage Douglass to be somewhat more tender-hearted in the application of his three-toed thong to the back of Dr Chalmers and others, lest he may yet find he is only renewing those applications to himself. ‘Send the money back,’ ‘send the money back,’ ‘send the money back,’ may yet, after all his pathos, be turned into ‘send Douglass back,’ ‘send Douglass back,’ ‘send Douglass back’ – to learn more correctness in his statements, and more justice in his conclusions.

Horrifying as his statements are, with all the lies he can muster, upon the sale of human flesh, &c., what will he say when demonstrated that he and his constituents are inducing a morality incalculably more immoral, savage, barbarous, bloody, and brutal than that which he affected so much to deplore? I can proceed no further at present than to reiterate my warning to all parties here to take time, and to withhold their opinions until both sides are heard. – I am, &c.,

VERITAS

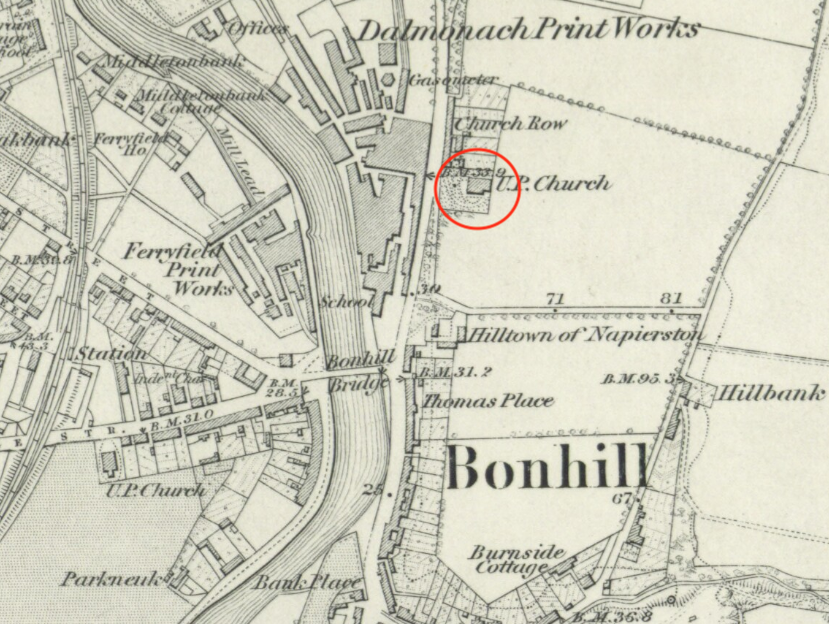

Bonhill, 2d April, 1846.

P.S. – The Free Church delegation in appealing to the proprietors of the Southern states, have acted with an impartiality, and upon principles of an enlightened philanthropy, for which all ages shall bless them, especially the toil-worn millions.

This was from the last edition of the Scottish Guardian – a free church paper.12 He had not the slightest doubt but that some members of the Free Church from their town would willingly aid in returning him to the United States as a slave. The Free Church had taken up the ground that slavery was not a sin in itself – that was a doctrine sustained in various departments of their church. He believed, however, that there was a large, a growing number who deprecated the receiving of the BLOOD-STAINED MONEY. He did not believe there was one present who would defend the character of the slaveholder, although this writer in the Guardian had done so. (Cheers.)

Who would defend the character of any one who would hold man as a slave? If slavery were not a sin, they might soon enslave the people of this country; for he believed that those who would defend the system, would not hesitate to do this. Would they countenance the Free Church, whose members countenance the slavery of the black man, while they would shrink back in horror from the thought of enslaving the whites? (Great cheering.)

He was going to call upon the dissenters of Scotland to shake off from them the men who held communion with the slaveholder. He would call on them to do this as followers of the meek and lowly Jesus. (Loud applause.) Every christian was bound to say to the Free Church, ‘Let go the slaveholder, or we will let go you – we will not form a part of the bulwark of slavery.’ (Continued cheering.)

Slavery existed in the United States because it was reputable. Nothing needed less argument to be proved than this – if it was disreputable, men would abandon it. He saw it reputable in the United States, because it was not so disreputable out of the United States as it ought to be. This was because its character was not well enough known. As much as he was bound to expose it, so much were they bound to expose it, so much were they bound to expose the guilt of holding on to the Free Church of Scotland, while she held on to the slaveholders. (Long continued applause.)

He saw that the evangelical alliance had said to the Free Church, ‘We won’t go with you while you hold communion with slavery.’ This decision at Birmingham would strike terror into the hearts of the slaveholders. It would be far more terrible to them than the writing on the wall was to Belshazzar. (Loud cheers.)

Where would the slaveholder go next? The Americans had lately annexed Texas – a country which breathed moral death. They were looking to Texas, that sink of pollution, and to Scotland. My friends, said Mr Douglass, THE FREE CHURCH MUST SEND BACK THE MONEY. (Immense applause.) He had a number of charges against the Free Church, and the truth of them no one, he was confident, could deny. They were as numerous as the commandments in the decalogue. He could have doubled them, and any one of them was sufficient to condemn that church – (cheers) – as unworthy of the christian sympathy of the people of Scotland. (Cheers.) Scotland ought to oppose the calumny. He asked if such a land as Scotland should be misrepresented by such a church as the Free Church of Scotland? (Loud applause.)

(Mr Douglass here read his ten charges against the Free Church; but as the substance of them is already before our readers in the speeches reported, we need not repeat them here.)

He called on the christian philanthropy of Scotland to speak out in the matter. Scotland was disgraced while the slave-money was retained to build churches on their free hills. (Cheering.) They would perhaps find the question put to Scotchmen when they went to the free states in America – Are you of those who countenance the taking of slave-money to build churches and to pay ministers? If you are, pass on the other side; if not, welcome, welcome! The line was being drawn between liberty and slavery. The time was coming when communion with the slaveholder would be deemed the foulest alliance – when they would look back with shame and confusion on their supineness in a matter so palpable. (Cheers.) The time was coming when men-stealing would be looked upon as worse than sheep-stealing. Had he not seen what he had seen since he became free, he might have gone to his grave with the idea that there was an implacable hatred of the black man implanted in the bosoms of the whites. God had made of one blood all nations of the earth, and he had commanded them to loose the bands of wickedness, to undo the heavy burdens, and to let the oppressed go free. (Great cheering.)

Mr Douglass then went on to state the case of George Latimer, who had escaped from slavery, and reached the state of Massachusetts. His master pursued him, and said if he got him he would kill him by inches. The slave was, however, protected, and his master was glad to escape from the fury of the people, which was raised against him. The laws of the state of Massachusetts were now much more in favour of freedom than they were.

Mr Douglass went on to say, that he was very much obliged to the meeting for their kind attention. They would accept his heartfelt thanks for the kind manner in which they had listened to him from time to time. He also thanked the committee, through whose energy and perseverance this honour had been conferred on himself and his friend Mr Buffum. He had become attached to the people of Paisley, and from whatever place he might be an ontcast [sic], he was confident he would find a home in good old Paisley. Mr Douglass resumed his seat amidst loud and protracted cheering.

The band here struck up in excellent style, ‘The Boatie Rows.’

The Chairman then said, that as he understood a part of the audience were anxious to have a shake of Mr Douglass’s hand, an opportunity would be afforded them as the meeting dismissed. A large proportion of those present then passed in front of the platform, and shook hands with Mr Douglass and Mr Buffum. The assemblage broke up about half-past eleven o’clock.

Renfrewshire Advertiser, 25 April 1846

Notes

- While the Slavery Abolition Act 1833 came into force on 1 August 1834, full Emancipation was not secured until the Apprenticeship system that replaced it was abolished on 1 August 1838.

- Thomas Campbell, ‘The Pleasures of Hope’ in The Poetical Works of Thomas Campbell (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1845), p. 27.

- Dickens’ most influential criticisms of slavery were made in American Notes (1842). See Tim Youngs, ‘Strategies of Travel: Charles Dickens and William Wells Brown’ in Travel Writing in the Nineteenth Century: Filling the Blank Spaces, ed. Tim Youngs (London: Anthem Press, 2006): 163-77.

- Two days earlier, Douglass had written to Horace Greeley, the editor of the New York Tribune, remarking that ‘I have been denounced by the “New-York Express” as a “glib-tongued scoundrel,” and gravely charged, in its own elegant and dignified language, with “running a much in greedy-eared Britain against America, its pepole, its people, its institutions, and even against its peace.”‘ Frederick Douglass to Horace Greeley, Glasgow, 15 April 1846 (New York Tribune, 20 May 1846; repr. in The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series Three: Correspondence, Volume 1: 1842–52, edited by John R. McKivigan (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), p. 104).

- On the campaign to end the racial segregation of the Massachusetts railroads (in which Douglass, Buffum and others were involved) see Elizabeth Stordeur Pryor, Colored Travelers: Mobility and the Fight for Citizenship before the Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016), pp. 76–102.

- See ‘Departure of Frederick Douglass, James N. Buffum, and the Hutchinson Family,’ Liberator, 22 August 1845.

- For a detailed account of Douglass’s outward voyage to Liverpool in 1845 see Alasdair Pettinger, Frederick Douglass and Scotland, 1846: Living an Antislavery Life (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018), pp. 3–6, 17–24. Some primary sources are reprinted here. The Captain’s name was Judkins, not Jenkins.

- O’Connell invited Douglass to address a meeting at Concilation Hall, Dublin on 29 September 1845. See Freeman’s Journal, 30 September 1845.

- Alexander Campbell (1796-1870) was a socialist and trade unionist and follower of Robert Owen. See J.F.C. Harrison, Robert Owen and the Owenites in Britain and America: The Quest for the New Moral World (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1969), p. 108. In Arbroath in February Douglass had denounced Chalmers’ ‘doctrine of circumstances’ as an Owenite doctrine.

- Buffum sailed back to the United States from Liverpool on 4 July 1846. See Manchester Examiner, 11 July 1846.

- On 14 March 1844 the Glasgow Emancipation Society held a meeting at the Relief Chapel, John Street, Glasgow ‘for the purpose of remonstrating against so flagrant a violation of the rights of humanity as is intended by the authorities of New Orleans, in the execution on the 26th of April next, of John L. Brown, for the crime of aiding the escape of a female slave’: Glasgow Herald, 18 March 1844. Meetings were also held Edinburgh, Birmingham and elsewhere.

- The letter was published in the Scottish Guardian, 14 April 1846. According to Iain Whyte, ‘Veritas’ was the pseudonym of Church of Scotland minister William Gregor: see Iain Whyte, ‘Send Back the Money’: The Free Church of Scotland and American Slavery (Cambridge: James Clarke & Co., 2012), p. 78.