I know Mike did a convincing impression of being a South Londoner. He made a pretty good stab at it. Others will testify to his life as a singer in the Jivin Instructors, devoted follower of Crystal Palace FC, and proud public servant with Southwark Library services.

But for me he was always from the North. Someone who may have parked his accent, but never lost it. Someone who never stopped loving the open spaces of the Pennine moors that backed on to the towns we grew up in, places you could escape to, and slip the parental knot.

I first met him one December morning when he padded into the kitchen at the hotel I worked in, starting a three-week holiday job. Shoulder-length hair and a droopy moustache. He used to say he saw my books before he saw me, after noticing a copy of Finnegans Wake on the window sill of the chalet I bunked in. The spines of my library ostentatiously facing out. It was a bare-faced lie. I would never arrange my shelves that way. But I forgave him for it as I always did – even for more wounding infractions, for he let me down many times over the years. And I was clearly not the only one.

We bonded that winter over music, literature, eccentric village pubs, dirty jokes, bad puns, and other people’s misfortunes. We formed an exclusive club of two he called the Anti-Christmas League and we did to Bing Crosby what the potato peeling machine did to those never-ending bags of KIng Edwards. And by the time he headed back to his Theatre Studies in Stratford-on-Avon an unmistakeable friendship had taken root.

A few months later I went back to live at home, enduring a series of factory jobs that would pay for shoe-string tours of Europe in between. But each summer Mike would head north again, like a migrating bird, to shelter me in his wings, as he made Lancashire come alive again, keeping me safe, even while leading me down lengthening avenues of mischief. Or ‘ginnels’ as we would have enjoying calling them. Because, wherever we went, something unexpected would always be round the corner, something bizarre, marvelous or hilarious.

It took me a while to realise they didn’t always happen by chance. I had no idea how we ended a long zig-zagging day at the Liberal Club in Summerseat on the wild fringes of Greater Manchester. It seemed just another predictable coincidence when it turned out that the young woman Mike seemed very comfortable with at the bar was his English teacher from school. We were miles from home and without transport and she offered to put us up for the night. Waking up on the sofa the next morning I was surprised – but enormously impressed – to discover that he had not slept in the spare room. Evidently Kath had introduced him to more than just Shakespeare.

I don’t know how much he learnt at college. I’d say he was self-taught, most of his reading being for its own sake, not for some course or other. He swept up many fragments of science, history, and geography in his net. Some of them still linger in my subconscious: the gregarious habits of the Manx shearwater, the vending machines built for Penguin books, the origin of the phrase ‘as dim as a Toc H lamp.’

I remember the time he stayed at my parents’ holiday cottage in the Lakes, carefully documenting in the Visitors Book our heroic drinking as much as the walks we did. Some goody two-shoes made me tear out the page before we left – just a little too vernacular for my mum and dad, I thought, but I also obscurely sensed it was worth keeping. In one entry, he gleefully mocked the pretentious over-wrought lyricism of a previous guest by writing simply, in capital letters, ‘ET IN ARCADIA EGO.’ A Latin phrase I think he picked up from Evelyn Waugh and which – as he delighted in explaining to me – meant that even amid the nymphs and shepherds of an earthly paradise, death is never far away. A memento mori that has extra poignancy now.

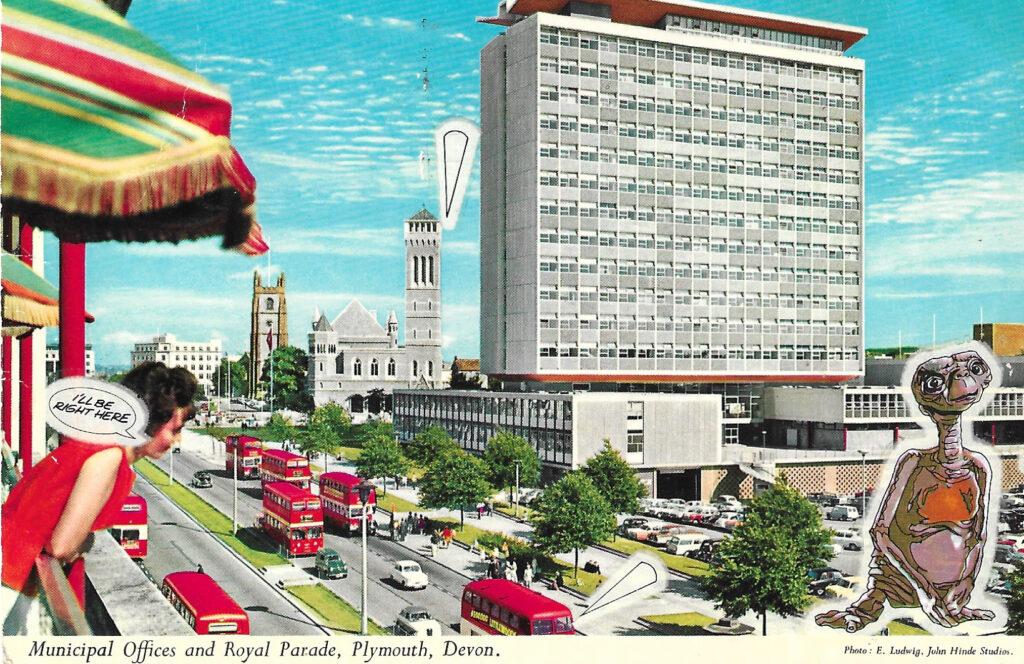

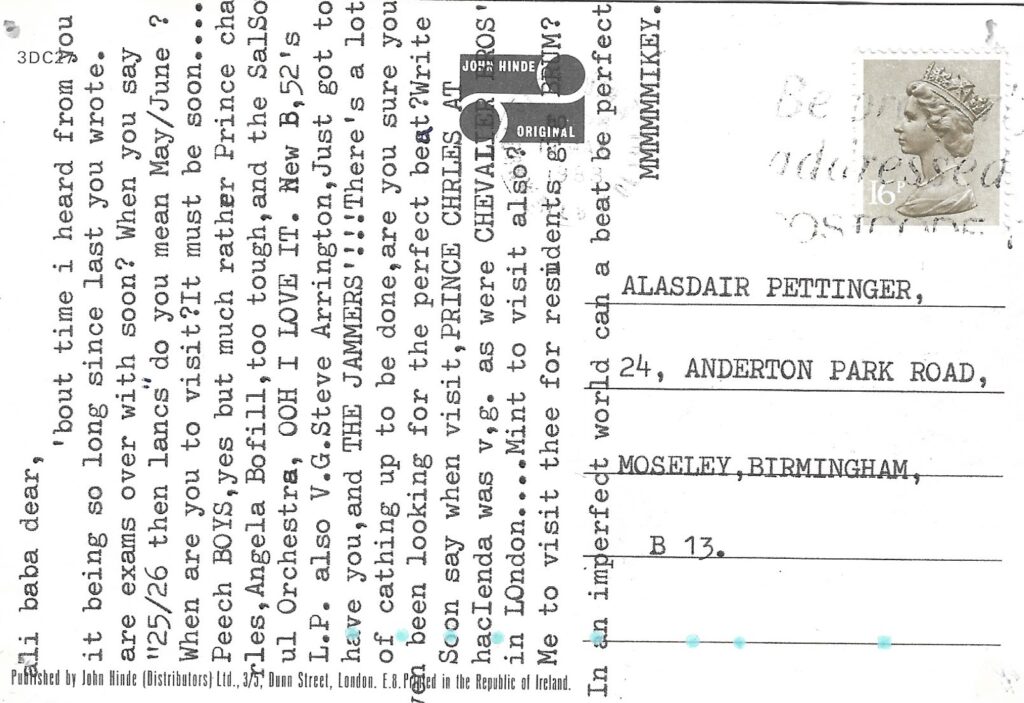

And I treasure another riposte of his I’ve kept, this one answering me, after I enthused about a new record I just bought, ‘Looking for the Perfect Beat’ by Afrika Bambaata. Typed on the back of a picture postcard featuring a laughably civic photo of Plymouth city centre, which he carefully defaced with inappropriate stickers, he seeks clarification of our summer plans, and bombards me with the music he’s been listening to: Angela Bofill, Prince Charles and the Beat Band, The SalSoul Orchestra, Steve Arrington, The Jammers, The Chevalier Brothers. ‘You sure you’ve been looking for the perfect beat?’ he asks. And then, in closing, another rhetorical question: ‘In an imperfect world, can a beat be perfect?’ Something I have pondered many times over the years.

He especially enjoyed springing his erudition on the unwary. Once, when we were hitch-hiking to Glencoe, drenched to the skin after an hour on the slip road and a sleepless night at a service station, we were picked up by a suit in a posh car. As we bundled ourselves and our rucksacks in the back seat, Mike recognised Beethoven on the radio. In his plummiest voice he boomed, as the Audi rejoined the carriageway, ‘Just in time for the minuet from the 8th symphony!’

It was the Allegretto from the 7th, but I didn’t say anything. Facts were always secondary to the dramatic effect. And to be sure some of the stories he told were decidedly iffy. Though when I checked them out, even the weirdest ones usually checked out. Approximately. For he had a remarkable memory, when it suited him. Only a few weeks before he died – which soon seemed like an age ago – he was enthusing about W H Auden, reciting lines, word-perfect, from what he called ‘that triumph of populism’, The Night Mail.

Speaking at the funeral, I would conclude with a poem. But no, not by Auden, not that one, made famous by John Hannah – but one of Mike’s own, written in the second blush of fatherhood. It’s called ‘Year Dot (after Sylvia Plath)’.