Jemma Neville

Jemma Neville

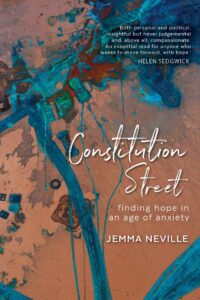

Constitution Street: Finding Hope in an Age of Anxiety

[Edinburgh]: 404 Ink, 2019

There are some other good ‘street’ books that engage with the residents by someone who knows the area well. Flatbush Odyssey and Isolarion come to mind, emerging from peregrinations in Brooklyn and Oxford respectively.1 But this is different. It is not structured as a single journey but organised thematically. Taking her cue from the name of the street in Leith, the author, who has a legal background, devotes each chapter to a human right (the right to life, to housing, to freedom of religious belief, and so on) illuminated through conversations with her neighbours, some of whom are close friends.

Among those she talks to are a casino manager, a puppet maker, a window cleaner, a pub landlady, a police officer, a doula, a founder member of Idlewild, a Buddhist nun who was once a girlfriend of George Best, a male blogger called Silver Fox in a Frock, and a postman who reveals how much he and his colleagues read the messages on postcards. Neville talks to them about their everyday experiences living on Constitution Street rather than probing them for back stories, perhaps keen not to invade their privacy. And the cumulative effect is a glorious hymn to what Paul Gilroy has called conviviality.2 But it’s also a celebration of the joys of handwritten communications.

Constitution Street is not all about the present. History peeps through in the shape of the Darien adventure, the compensation paid to Leith slave-holders after Emancipation in the West Indies, the 1560 Siege of Leith, the Leithers killed in the rail crash of 1915, and the lightning plebiscite of 1920 that led to the town’s merger with Edinburgh despite the large vote against it. But the best stories are of the more recent past: a public clock unwittingly unplugged by a cleaner, how an alligator came to be sold from the boot of a car, the discovery of an ancient burial ground during tramline excavations.

Neville is as at ease describing the breathtaking evening view from a 16th floor flat as she is capturing the cast of characters at the Port O’ Leith bar. I liked the Perecquian inventory that precedes the main body of the text, listing things seen on a walk. The writing is often lifted with poetic touches. She recalls an umbrella abandoned in a puddle in Barcelona, ‘its spokes bent upward like jabbing fingers demanding of the sky Votarem!’ (p237). She transcribes an interview, ‘carefully picking the exact letters from my keyboard like the harvesting of these delicate, precise leaves from a twig of thyme scenting the air’ (p100). Leith docks are compared to ‘an abandoned fairground’ (p163). She has a fine ear for the contrast between daytime and nocturnal sounds and Constitution Street ends with a lovely pitch-perfect early-morning epilogue.

Her cultural frames of reference include (somewhat predictably) Trainspotting and The Proclaimers, but W H Auden, Edward Hopper, Leonard Bernstein, Nan Shepherd, Robert Burns, Virginia Woolf, James Joyce also make an appearance. But if she occasionally nods to other places round the world – Catalonia, Iceland, Rojava – we never lose sight of Leith for long. A hand-drawn, illustrated map (by Morven Jones) helps to orient the reader. And the chapters are broken up by black and white photographs (by Rob Smith, who deserves a more prominent credit), picking out intriguing details of the built environment, often small decorative features that go unnoticed by passers-by – tiling, brickwork sculpted marble – complementing the text perfectly.

The thematic structure (emphasised by the chapter titles, ‘The Right to Life’, ‘The Right to Education’, and so on) runs the risk of feeling imposed on the material. But apart from the overlong introductory sections and the sometimes flat endings to the chapters, it works well and reads naturally. Neither sentimental nor cynical, Constitution Street salutes its readers with honesty and warmth.

- Allen Abel, Flatbush Odyssey: A Journey Through the Heart of Brooklyn (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1995); James Atlee, Isolarion: A Different Oxford Journey (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007).

- Paul Gilroy, After Empire: Melancholia or Convivial Culture? (London: Routledge 2004).